21 May The Low Down on Low Back Pain – Part 1

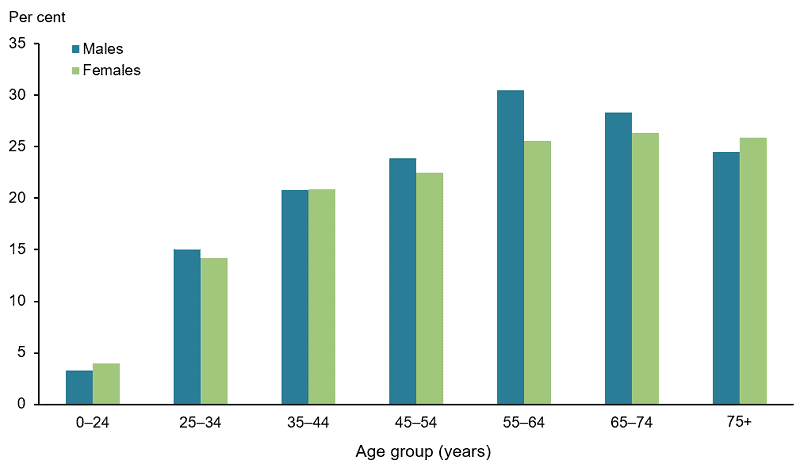

How common is lower back pain?

Low back pain is the most common musculoskeletal complaint presenting to GP’s in Australia. Research predicts it will affect between 1 in 7 and 1 in 4 Australians in their lifetime and between 10-40% of those will develop ongoing symptoms. It appears that back pain prevalence is more widespread in western and developed nations and the rate of people developing ongoing concerns is only increasing. Persistent low back pain can be one of the most frustrating presentations for clients to present with, it affects nearly every aspect of their daily lives, and reduces their ability to take part in the aspects of their life that they love. So why is back pain so common, and why does persistent low back pain appear to be becoming more and more common? With so much research around the world being done (including one study that actually investigated whether wearing wool underwear improved symptoms – surprisingly their results found that it did!) how is it still one of the biggest issues plaguing modern society.

What structures make up the lumbar spine?

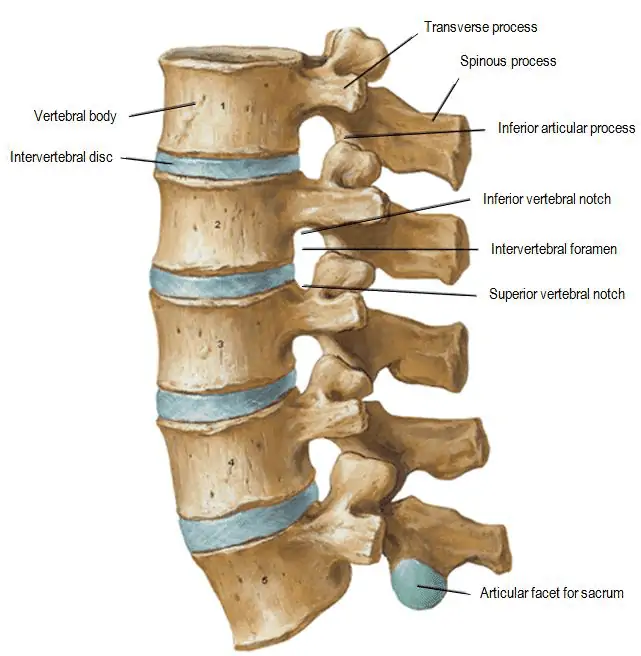

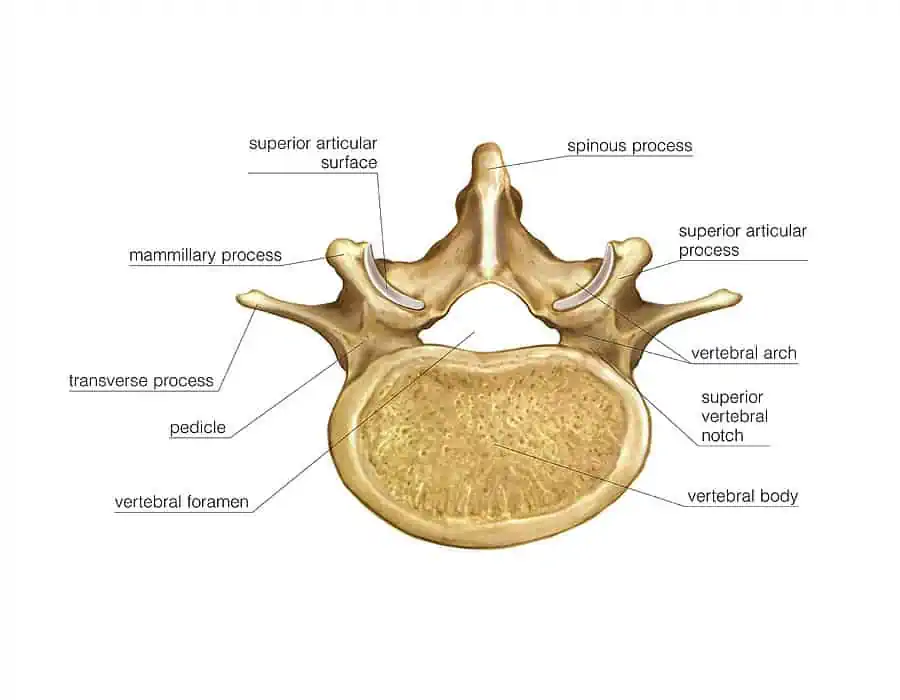

The spine is an incredibly strong and robust structure consisting of ligaments, bones, joints, nerves, as well as overlying muscles to provide support. The palpable section of the spine that lies through the middle of the back are the spinous processes. These segments protrude from the vertebral body towards to surface of the skin. Through different segments of the spine (cervical, thoracic, and lumbar) the spinous processes protrude at different angle. What this allows for is the freedom of movements through different segments as well as prioritising certain movements.

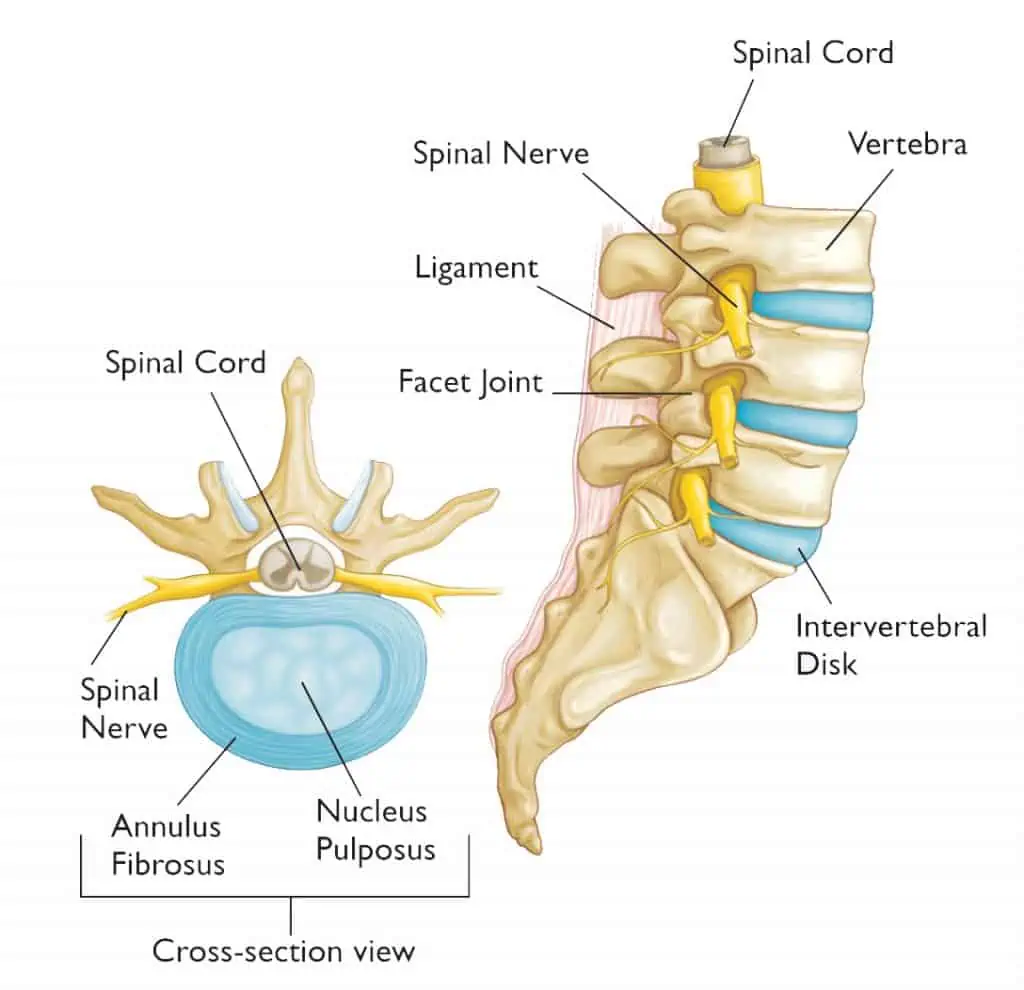

The vertebral body sits as the core main structure of each level of the spine. These are stacked on top of each other and there is the discs between each of the levels. The vertebral body is a strong structure and is often unlikely to be injured unless in the case of a direct force travelling upwards through the spine – think landing heavily on the ground, or a repeated higher level force such as riding on a horse.

As we mentioned just above the discs sit between each vertebral body. The disc is comprised of two structures, the tough outer layer known as the annulus fibrosis, and the softer inner portion known as the nucleus pulposus. Due to the outer layer of collagen fibres provided by the annulus fibrosis discs are surprisingly strong structures. Previous thought patterns suggested that as we bent forwards a disc bulge would move in and out – the description of biting into a jam doughnut was used where when you bit into the doughnut the jam would push out from the other end. Fortunately this line of thinking has well and truly passed and we know that this is no longer the case. In the vast majority of cases, disc bulges that are found on imaging have likely been present for a while (in some cases likely years). This isn’t to say that disc bulges can’t be a source for symptoms – but more to suggest that potentially disc bulges are not the culprit in many cases of back pain and don’t deserve the bad reputation they have been given.

Much to everyone’s common knowledge, the spine provides the support and structure around the spinal cord. This also allows for the nerve roots to be supplied to the body, the lumbar spine specifically provides the nerve supply for the lower limbs. Each nerve root originates from a segment of the lumbar spine, understanding the role these nerve roots can play and understanding their sensory and motor contributions is vital to being able to clinically reason a potential disc bulge with nerve root compression on imaging. If that finding were to be present but clinical symptoms and testing weren’t able to be correlated the relevance of the finding could be questioned.

Facet joints are the other common structure referenced within imaging and are a common source of symptoms. Transverse processes are the structure that protrudes to the left and right from each vertebral body and adjoin to the facet joint from the level above/below. The transverse process isn’t quite as strong as the vertebral body and can be a source of symptoms particularly in young athletes competing in dancing, cricket, or gymnastics due to the nature of the sport and the loading patterns to the back. The facet joint is the articulation between the different levels of transverse processes and allows for freedom of movement along different axes. Similarly to the spinous processes, as you move through different segments of the spine, these protrude at different angles to allow for more specific movement patterns related to that specific segment of the spine.

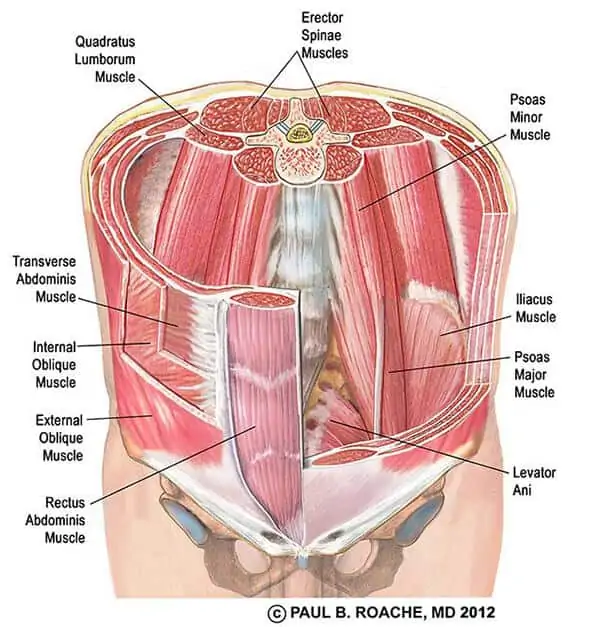

The muscles surrounding the lumbar spine provide a great deal of support and assist in offloading joint and nerve structures. Having the strength but also the control of these muscles is vital to succeeding in rehabilitation. There are many many muscles, with relatively 2 distinctions – smaller stabilising muscles, and larger prime movers that can produce power movements. Previous thought patterns suggested that the role of the transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus were key to rehabilitation – and were potentially the cause of back pain. Unfortunately research has been quite inconclusive as to whether retraining these muscles specifically and in isolation is the “magic pill” to curing back pain. In my personal opinion they are important but no the be all and end all, it’s important to consider function and movement patterns rather than just isolating specific muscles as “dysfunctional”. Some studies have been able to find that a general exercise program can lead to a similar effect in regards to strengthening and hypertrophy of these two muscles without any specific work related to those two muscles.

What are the risk factors for developing low back pain?

The predominant risk factor for an episode of back pain is a previous history of back pain, whether that be a history of one or two acute episodes or a history of persistent lower back pain. Unfortunately, this risk factor is not modifiable, if I could go back in time and rid people of their medical history I’m sure I’d be a millionaire by now. Another risk factor for lower back pain is a sedentary lifestyle, research indicates that the more active your lifestyle is the less likely you are to experience an episode of lower back pain. Poor sleep, poor nutrition, and increased stress are other common risk factors, though not as large as a sedentary lifestyle. These are often factors that compound upon each other. If you consider a bucket that is filled halfway this would be your starting level of risk for an episode of back pain. If I then add in 3 nights of poor sleep, increased stress in both work and personal lives, and then I try to do a lot of landscaping and gardening on the weekend that I wouldn’t normally do I have then filled this bucket up quite a lot. On Monday morning I may do something inconspicuous like take a dish out of the dishwasher and hurt my back. Many people would blame the bending forwards and picking up the dish – but I would say the cause was the increased physical and mental stressors from the week prior that resulted in an increased risk profile for an episode of acute lower back pain.

Many people ask whether poor posture is a risk factor for back pain. This actually takes a lot more explaining than many people expect as they often assume that the answer is an unquestionable yes. Currently, no research has been able to identify a link between poor posture and back pain (or any pain for that matter whether that be neck, shoulder, mid or lower back). But how do so many people report that sitting in poor postures is a cause of their pain – because this is something that so many people have told me in my years of working. Whilst there is no research to solidly stand behind my theory here but I am of the belief that it isn’t certain postures that cause pain, it’s sustained postures. And more often than not the sustained posture that people keep is often a poor posture – think slumped forwards, shoulders rolled forwards, and chin protruding forwards. If I were to sit like that for 5 minutes I wouldn’t get back pain, but if I didn’t vary my posture throughout the day the same tissues are under the same stressors for hours on end, eventually something is going to get unhappy. Inevitably this leads me to the conclusion that being able to vary positions and adapt to different postures throughout the day is the optimal strategy when try to adopt a “best posture”.

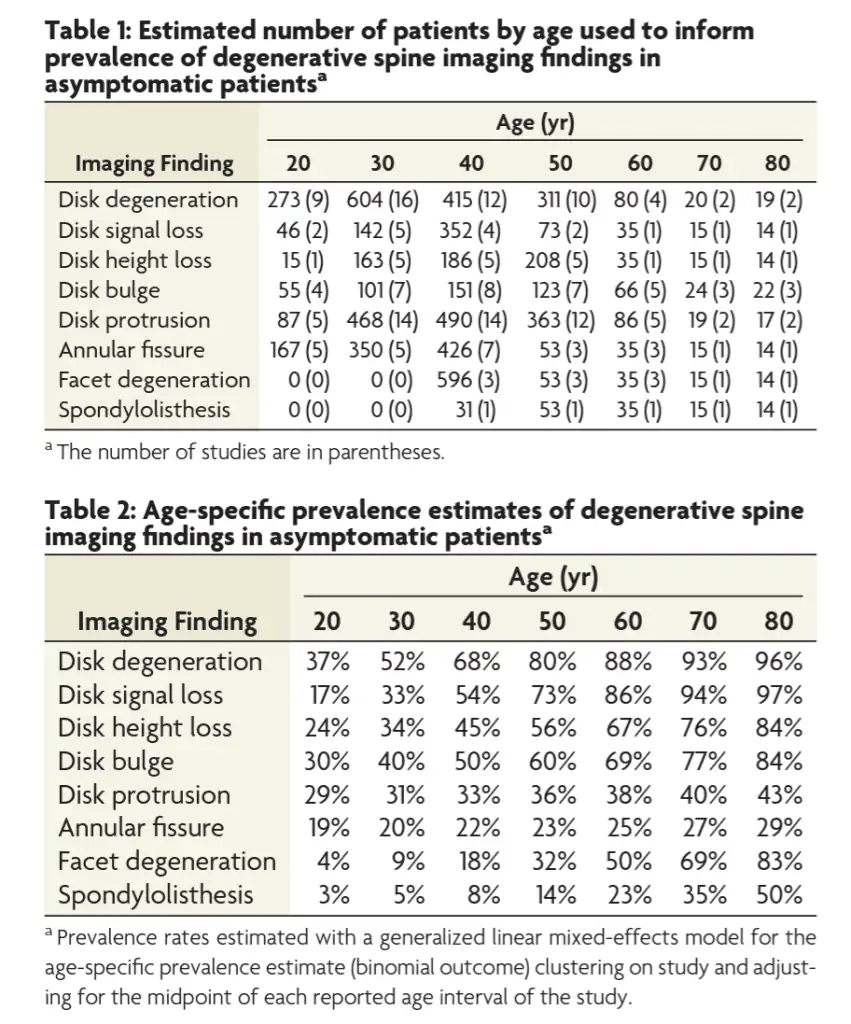

Imaging is another common difficult one to explain to clients. So often clients report that their MRI 5 years ago found a disc bulge so that must be the cause of symptoms again. Fortunately, most disc bulges can spontaneously resolve themselves. Secondly, it is quite difficult to clinically correlate findings on a scan to clinical symptoms, there is just too many potential structures within the lumbar spine that may cause symptoms. Thirdly, so many of these findings (disc bulges, pressure on a nerve root, joint degeneration) are found in the vast majority of the population who DON’T have lower back pain. This leads us to the question of why does 1 person with a disc bulge have back pain but another person doesn’t? I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve seen clients with lower back pain who have no findings on imaging. It’s incredibly important as health care practitioners that we adequately educate clients on what is on the imaging and whether it is clinically relevant. And before going for the imaging a discussion surrounding what the imaging is looking for should be had, imaging should be utilised to look for a specific diagnosis rather than just looking for something. Where imaging may be useful in a proactive manner, is that the more findings you have on imaging results the more likely you are to have a future episode of lower back pain. All is not lost though, if you optimise the modifiable risk factors (weight, exercise, sleep nutrition etc.) you will do as much as you can to reduce that risk.

What can cause low back pain?

The most common causes of lower back pain that I see within my work are facet joint injuries, discogenic pain, and muscular issues. Let’s dive down into each of them:

Facet Joint Injuries

This and discogenic pain are probably the most common presentations that I tend to see, facet joint injuries are quite distinct in their presentations. On clinical testing clients won’t like to extend their back, and once you extend, rotate, and bend down to the side that is often their least favourite. People may often report that they don’t like laying on their sore side or on their back when trying to sleep at night and may roll onto their non sore side and potentially place a pillow between their knees. I would say this presentation is often a slower build up of symptoms over a few days but can present as an acute onset. It is unlikely that there is going to be any nerve pain referral with these presentations.

Discogenic Pain

This is arguably the most common and most recognisable presentation for lower back pain. It is the classic presentation of a client who does not like to bend forwards and potentially has some nerve pain referral down their leg or into their hip. I would say in most cases this presentation has an acute onset where someone picked up a dish, a pen, or something from the floor and then had a sharp onset of pain. It’s important to remember that this sharp onset of pain isn’t the disc bulging right at that moment in time, but it more than likely is just an increase in pressure on what is a sensitive structure and the brain determines that it doesn’t want that so creates an acute pain response. Clinically these presentations often do not like to bend forwards, may present with nerve pain referral, and often find it difficult to find comfortable positions.

Muscular Issues

I’m going to be a bit controversial here and rename something that I don’t like the name of, most cases of lower back pain are diagnosed as what’s called “non-specific lower back pain”. I totally understand why research indicates that it’s difficult to identify a structure but often we are able to identify a pattern to the symptoms as such I don’t really like calling it non-specific. But sometimes I get clients who don’t present with a particular pattern to their symptoms and present with acute muscular spasm around the lumbar spine, or present with increased tightness to the hip flexors, or gluteals, that may be altering movement and control around the pelvic and lumbar spine. These are just examples of some thing that may be labelled as “non-specific lower back pain” but things that I believe have a diagnosis and have a treatment plan and pathway to recovery.

When should I see my doctor?

Most clients will either present to their local GP initially or present to their physiotherapist, chiropractor, or osteopath (I may be a little biased as to which of those 3 I would choose but ultimately as long as there is a plan to recovery and you are given an individualised treatment and exercise program that’s the best option). In my experience, not too many cases of lower back pain need to go see their GP. More often that not I would recommend it for clients if they find that over the counter pain medications are unable to adequately settle their symptoms to allow them to progress with physiotherapy and an exercise program. The other two situations where I would refer on for a GP review would be if I believe imaging is necessary and may change the treatment pathway, or if I believe that it may potentially be a non musculoskeletal issue requiring potential medical management.

Symptoms that require urgent care

Some symptoms and presentations often require further investigation, as physiotherapists we are first contact practitioners, that means that essentially anyone can walk in off the street and see us. So we have to be acutely aware of potential other non-musculoskeletal causes of low back pain. Keeping on top of these is quite important as they don’t come up often but you need to catch them if they do pop up. A 2020 study recently assessed common symptoms and which ones required further investigations or were related to non-musculoskeletal causes. Their findings indicated that saddle anaesthesia, bladder and bowel concerns such as urinary retention or other symptoms, a history of tuberculosis, fever, abdominal aortic aneurysm, writhing pain, unexplained weight loss, intravenous drug use, and flank pain were the most common reported symptoms/issues that correlated to an escalation of care.

Latest Blog Posts

- Lifting Technique “Never Lift with a Bent Back” – Why Those Words Make me Shudder

- When should I see a Physio?

- Adductor Strains – A Footballers Worst Nightmare

- Hamstring Strains – Frustrating, Recurrent, Our process for how we can help you

- Gluteal Tendinopathy – It’s a Real Pain in the Ass

How can we help?