14 Sep Gluteal Tendinopathy – It’s a Real Pain in the Ass

What are tendons?

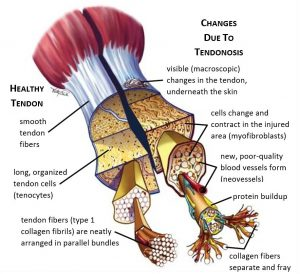

Tendons are the link between muscles and bones and allow your bones to move as your muscles contract and relax. They are able to absorb high levels of force and help prevent muscular injury during higher-force activities like hopping, jumping, or sprinting. Tendons are predominantly made from collagen and also contain nerves and blood vessels. They are strong structures that are highly resistant to tearing but aren’t stretchy or flexible.

What is tendinopathy?

Tendinopathy is a term typically used when there has been an overload injury of a tendon. You typically wouldn’t use this term for someone who has sustained a tendon tear or rupture as they are completely different processes. Tendinopathy will typically develop over time and often without symptoms for a long period of time before you feel them. Often, because they develop relatively slowly, some people may put off the pain at the start and just continue what they are doing.

The Tendinopathy Continuum

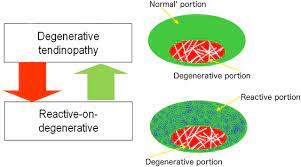

Jill Cook and Craig Purdam, two Aussie physios developed what they termed the tendinopathy continuum. It is relatively seen as the gold standard for our current, but somewhat limited knowledge of tendons. Previously there used to be an understanding that tendinopathy was an inflammatory condition – hence the name tendonitis, but according to most recent research the appears to be such a small amount of inflammatory markers that it’s almost not even worth mentioning. Jill and Craig proposed a 3 stage continuum that tendinopathy develops along, so let’s dig into it and then talk about how it fits in with gluteal tendinopathy.

Reactive

Reactive tendinopathy occurs when you have an acute tensile or compressive overload and is proposed to be a non-inflammatory process within the cell and matrix. Ultimately, the tendon will adapt and thicken to increase the cross-sectional area to better tolerate the load or adapt to the compressive forces. The collagen integrity of the tendon is well maintained but there may be some separation of tendon fibres. The reactive response is largely a short-term adaptation to overload that thickens the tendon with the aim of reducing stress and increasing stiffness. The tendon is able to revert out from this stage provided the overload is sufficiently reduced or there is enough rest between sessions.

Dysrepair

Tendon dysrepair could also be termed “attempted healing”. There are similar changes seen in the reactive tendinopathy change however there is a greater breakdown within the cell matrix of the tendon. The major change is an increase in the number of cells (mostly protein production – proteoglycans and collagen). An increase in proteoglycans increases the separation of the collagen and increases the disorganisation within the tendon. Some of the changes seen at this stage ultimately cannot be reversed, but this does not indicate that your tendon is “damaged” “fragile” or “weak” by any means.

Degenerative

The changes that we see in the tendon dysrepair stage are simply increased in this stage. The main progression that we see is areas of cell death. A degenerative tendon could simply be described as a tendon that isn’t useful. The tendon within this area is disordered, filled with neurovascular structures and matrix breakdown products and little collagen is present. There is largely no chance of reversal once this stage of the tendon continuum has been reached. In good news though these areas of degenerative tendon are simply just areas that won’t load, the amount of healthy tendon significantly outweighs the amount of degenerative tendon in almost all cases.

A Degenerative tendon – That sounds terrible

Don’t worry I totally get it, degenerative tendon probably wasn’t the best word for them to choose seeing as we then have to explain it to our clients. But everybody has degenerative tendon. It is in essence a sign that you have used your tendon in your lifetime – particularly during your teenage years. But degenerative tendon is essentially tendon that isn’t useful to us, it can’t be used, just think of it like a little dead spot in your tendon. You still have a vast amount of completely normal functioning tendon surrounding it. The analogy that is often used is to think of a doughnut, in the middle is the degenerative tendon and the doughnut itself is the healthy tendon. We can’t treat or fix the degenerative area, so we have to focus on the healthy tendon surrounding it and make it as strong and load-tolerant as possible.

What has this got to do with my hip pain though?

At the end of the day, most clients presenting with gluteal tendinopathy are women aged between about 40 and 60. Some may find themselves solely in the reactive tendinopathy group but most will find themselves with a component of tendon degeneration. I think it’s incredibly important for my clients to understand this process and know that their tendon is healthy, it’s simply been used throughout its time. Exercise is the avenue to improve tendinopathy symptoms – work the doughnut and improve its load tolerance and forget about the hole in the middle.

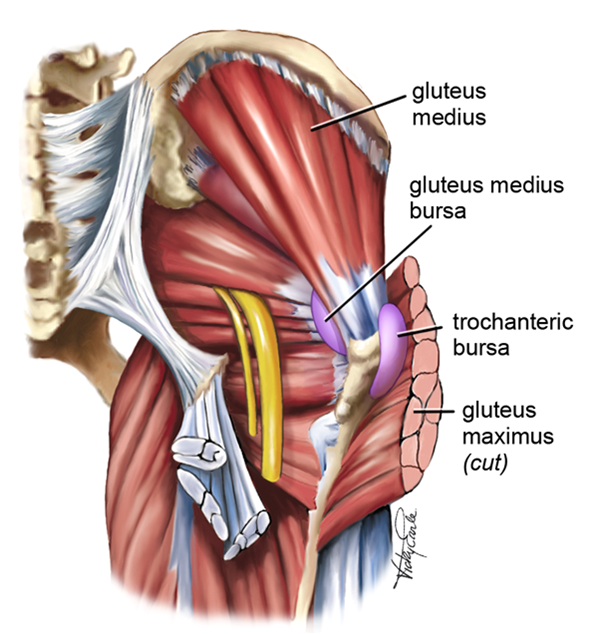

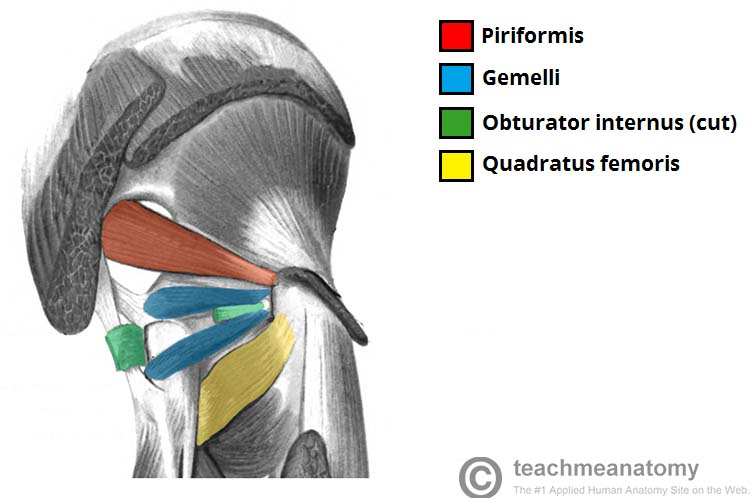

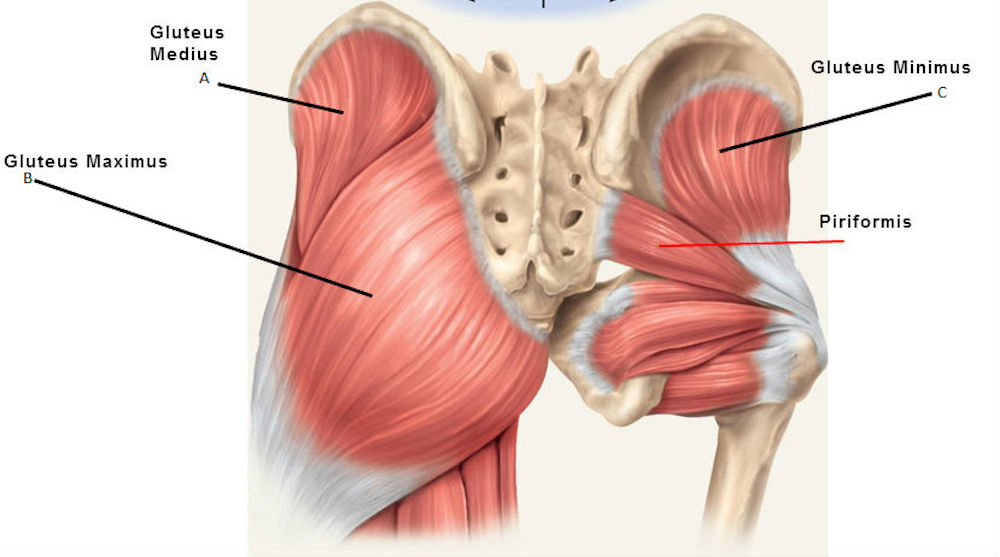

What is the relevant anatomy of the area?

The most common landmark to use in a clinical and educational aspect is the greater trochanter. This bony landmark is the bony point of your hip on the side of your leg and forms the junction between the neck and shaft of the femur. With regard to gluteal tendinopathy, you should pay particular attention to the tendon attachments. These include: the piriformis, superior and lower gyrus, internal and external obturator, and the gluteus maximus and medius muscles. This is a large number of muscle attachment sites! Beneath all of these tendon sites a range of bursae. Bursae are fluid-filled sacs that essentially act as friction reducers. You wouldn’t be having a great time if you had tendons rubbing directly on bony prominences.

The important point to remember about the greater trochanter is it is protruding a fair way from the shaft of the femur and creates a pivot point around which the tendons are able to move. In cases of bony prominences like this, tendon compression can be very easy to induce. Positions like crossing your legs with one over the top of the other in sitting or standing are one of the most common aggravating positions for clients and are due to the compressive forces placed upon the tendon and bursae when they are stretched.

These are the range of structures that can cause symptoms, and often they fall under the definition of Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome. This is somewhat an umbrella term of lateral hip pain as it can be difficult to truly differentiate a case of trochanteric bursitis and gluteal tendinopathy in some clients and the management pathway is relatively similar.

Is it Gluteal Tendinopathy or Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome?

These terms are somewhat synonymous in physiotherapy these days. What some people may diagnose as gluteal tendinopathy others may diagnose as greater trochanteric pain syndrome. My belief is that further imaging is needed in most cases to truly attempt to differentiate between the two. Even then it is far from certain that if you have trochanteric bursitis on ultrasound that it might not be a case of gluteal tendinopathy. It’s usually for that reason that I tend to operate more under the greater trochanteric pain syndrome diagnosis with consideration for particular treatment pathways such as a corticosteroid injection if there is an enlarged bursa that may be symptomatic.

Who gets Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome?

40-60-year-old females

This forms the majority of the cases out there of gluteal tendinopathy. There are a number of reasons for this, particularly in the risk factor category below. Women in particular are at a greater risk of gluteal tendinopathy than men purely based on their anatomy. Women are born with a greater Q-angle (the angle of the femur – a greater angle indicates wider hips), as such this creates a greater compression force at the greater trochanter. Older women are also at greater risk due to the onset of menopause. Menopause causes a range of changes within the body that can affect tendons and it is relatively accepted that the onset of it raises your risk of tendons throughout your body.

Athletes

This is probably your second most common category, unfortunately, I fell into this category earlier this year following increasing my running distance and speed too quickly. That’s a pretty typical way for those cases to happen. Just combine it with some weakness to the gluteus medius and maximus causing some changes around the lumbopelvic region and you are on the highway to overloading the gluteal tendons.

What causes Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome?

Significant increase in training load

When looking at younger athletes this is pretty much always the reason for symptoms starting. Getting a little too ambitious before a running race and training a little too hard and too often is the main culprit. Loading your tendon structures too much too fast doesn’t allow them time to turn over and recover between sessions. Allow time for your body to recover and gradually build up how much you are doing to avoid getting in trouble. As always listen to your body, particularly if you are just starting out.

Increased compression

Compression is often reason number one for symptoms in older age clients. Too much time with your legs crossed, sleeping on your hip all night every night, and doing too many glutes stretches to try and stretch out your lateral hip pain will catch up to you. Avoiding compression is the key to getting rid of your symptoms and often avoiding them in the first place.

Poor functional control of the lumbopelvic region

This is the ultimate equaliser between the two groups and is present in almost every case of gluteal tendinopathy I see. Weakness through the hip and lumbopelvic region places a vast amount of stress on the gluteal tendons and bursae. This weakness causes a range of functional movement pattern changes such as a Trendelenburg sign, where the opposite hip drops when you are standing on one leg. Alternately you could have increased rotation of your femur – often this will show as your knee drops inwards. Both of these signs are commonly seen in active people such as runners, but also in older people, particularly when they are walking up stairs.

What might increase my risk of developing gluteal tendinopathy?

Female

Unfortunately being female is one of the bigger risk factors for developing gluteal tendinopathy. Women are born with naturally wider hips for the whole child-birthing thing, this creates greater tension on the gluteal tendon attachment site. I would also somewhat be of the belief that childbirth may have some impact. Previously rehabilitation following childbirth wasn’t done as routinely as it was today. This could have led to an impact on abdominal muscle rehabilitation and control around the hips and lumbopelvic region potentially increasing the risk profile of developing lateral hip pain later on in life.

Menopause

I’m not going to claim to be a women’s health expert here by any means, so if you believe this may be a significant factor I would be recommending you have a discussion with your GP. Oestrogen plays an important part in the turnover of collagen in tendons. Unfortunately, during menopause, oestrogen levels drop off quite significantly. This results in changes to how the tendon turnover process happens, so the process takes a little bit longer. Sometimes you might have to be a little nicer to your body once you have reached this point in time in your life.

What parts of the body does gluteal tendinopathy affect?

The hip and pelvis are the two primary areas affected but the knee may also be affected in chronic cases. The main area of symptoms related to gluteal tendinopathy is centred around the greater trochanter and gluteal tendons. Symptoms may refer down the outside edge of the thigh. Knee symptoms might develop in longer-term cases where there has been an ongoing period of adaptation to shift the load away from the gluteal tendons. Lower back pain may also be a secondary complaint but not all that common.

Common presenting symptoms

Pain

Pain is pretty much the primary reason why anybody sees a physio. The area of the pain can be pretty variable in gluteal tendinopathy, I would say in most cases it is pretty isolated to the greater trochanter or in the immediate vicinity. Some other clients may experience a radiating and sometimes burning or throbbing sensation spreading down the outside of the thigh. Whether this is driven by nervous system sensitisation, muscular effects and adaptations, or from the widespread nature of the symptoms of bursal tissue can change from person to person. The pain is generally pretty intense around the greater trochanter and gluteal tendon area particularly to touch or having direct pressure on it. Often I would say most clients describe it as a throbbing sensation or occasionally a burning and aching sensation.

Functional activities that make it worse

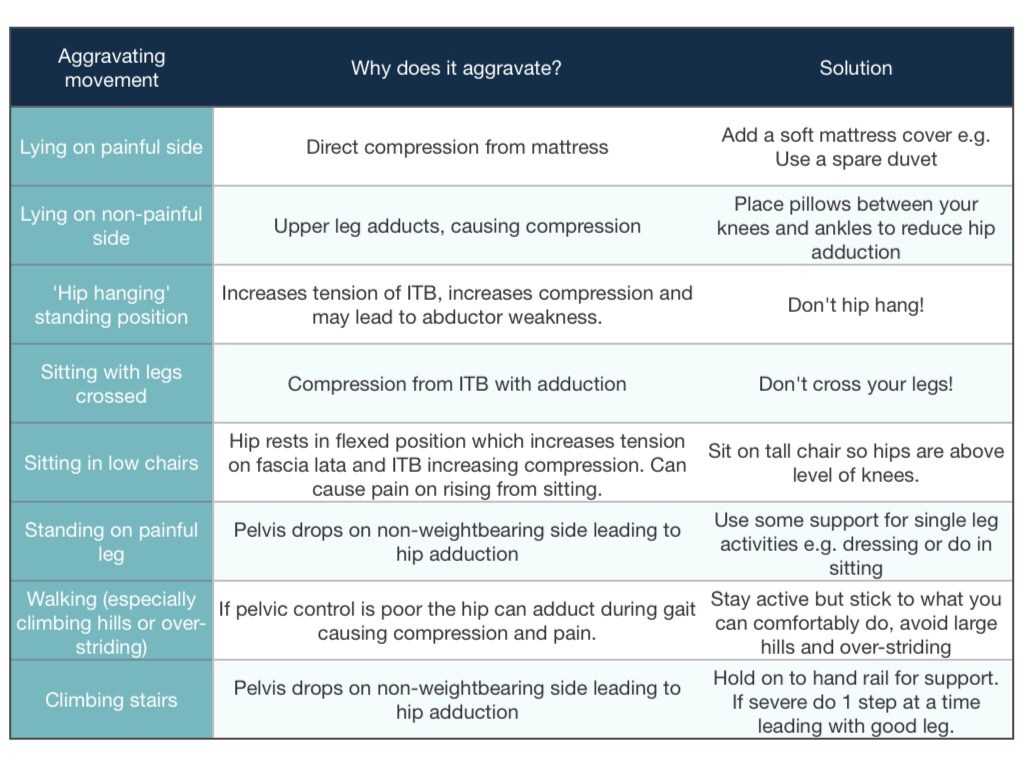

Stairs

This is probably the most common aggravating factor for clients with gluteal tendinopathy. It requires a single-leg stance whilst producing enough force to then propel yourself up to the next step. I remember when I had a case of gluteal tendinopathy earlier this year I had to resort to taking 1 step at a time, honestly, it was terrible and I hated it but my hip needed to offload itself a little to settle down. Keep an eye on whether going upstairs or downstairs is worse as that is useful information to be able to pass on.

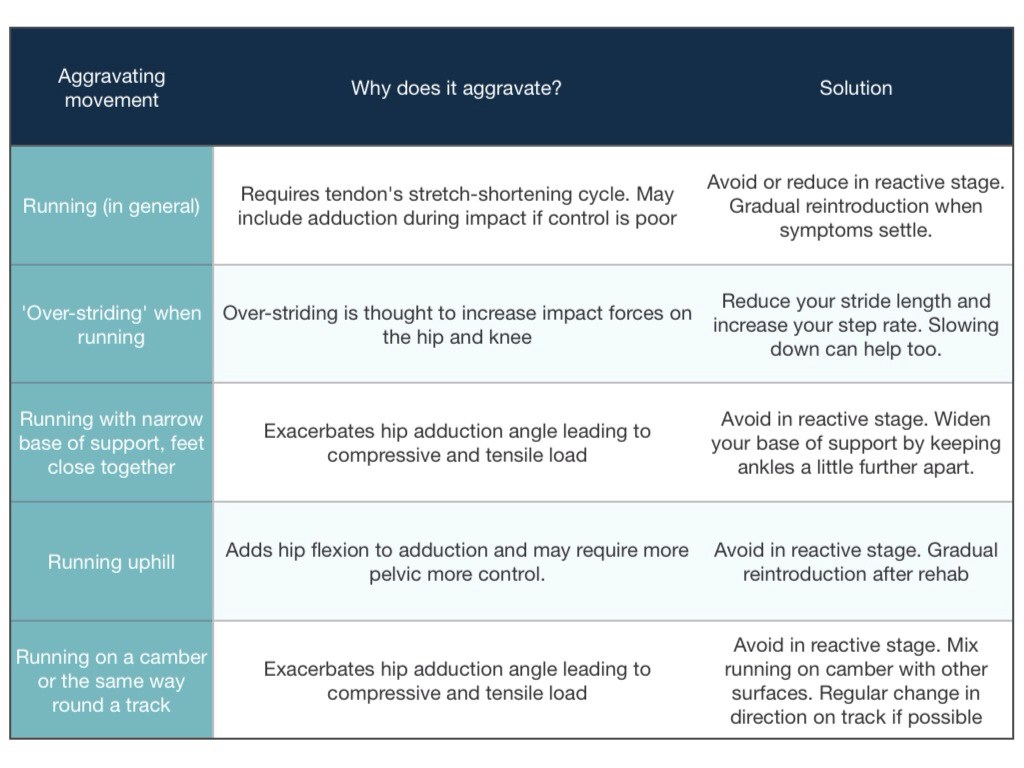

Walking

In general, this isn’t always fun, but I’m more talking about clients that utilise walking as a form of daily exercise. It usually takes a fair distance of walking in most cases of gluteal tendinopathy to become symptomatic or cause symptoms afterwards. A couple of useful metrics to keep track of are how far or long can you walk before symptoms, what effect the terrain has, what effect speed has, how sore is it afterwards and then how long it takes to settle.

Sleeping

Probably the biggest complaint clients make, this is a really common complaint for clients with trochanteric bursitis rather than true gluteal tendinopathy. The bursa is compressed in a lot of sleeping positions, particularly if you are lying directly on that side. Gluteal tendinopathy can be sore with sleeping but I’d say it’s a little less common and more often than not it’s when someone is sleeping on the opposite side and is compressing through the gluteal tendon complex. Utilising a mattress topper can help to take a little bit of the direct pressure away from it and reduce pain, otherwise, it is a matter of finding a comfortable position to sleep in.

Hills

Just like walking on flats but harder work for your legs, hills aren’t a gluteal tendinopathies best friend by any means. Walking uphill takes significantly more force production from your legs and particularly producing muscular drive from your glutes. If you are a little weak or lack a little control around the hips and pelvis, hills will be something you really don’t like. Taking it back to flats and reducing your distance while you build up your strength and endurance is your best path forwards to getting back to tackle those hills.

How is a diagnosis made?

Subjective Examination

Most cases of gluteal tendinopathy can be diagnosed following a thorough subjective examination. Objective tests should be utilised to confirm the diagnosis, assess your functional capacity, and rule out any other potential diagnoses. During your subjective examination, we’ll delve into a few key things. The first is always the history of your symptoms. We want to have a thorough understanding of how the symptoms first started and how they have progressed since then. After this discussing the pain is our next step, getting a thorough understanding of what it feels like and how it affects you in both a physical and psychological aspect is vital. The psychology of pain is something that is often glossed over in physiotherapy but it’s key to really understanding our clients. Getting an understanding of your exercise habits and routines is another key piece of information, particularly if there have been any recent changes occurring around the time that symptoms started. Lastly, understanding your goals and what you want to achieve is the final piece. Without this information, developing an independent plan is near impossible.

Objective Examination

When doing an objective examination for a case of greater trochanteric pain syndrome there are 8 key tests to perform based on the latest research.

- Palpation of the greater trochanter and gluteal tendon region.

- Combined flexion, abduction, and external rotation of the hip

- 30-second single leg stand

- External de-rotation test

- Combined flexion, adduction, and external rotation of the hip

- Combined flexion, adduction, and external rotation of the hip with resisted hip internal rotation

- Passive end-range hip adduction in lying

- Passive end-range hip adduction in lying with resisted hip abduction

All of these tests together are adequately sufficient to determine a case of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Determining between a case of gluteal tendinopathy and a case of trochanteric bursitis I believe comes down to differentiation during the subjective examination rather than during the objective.

In addition to these tests, assessing your functional capacity with movements, loading patterns, and positions could include:

- Squat

- Single leg squat

- Stairs (both up and down)

- Walking

- Walking uphill

Imaging

Ultrasound is pretty much the best choice imaging for gluteal tendinopathy. It is sufficient enough to assess the integrity of the gluteal tendon complex and diagnose any tendon tears, and can assess deep enough to assess the bursae and potentially diagnose a case of trochanteric bursitis. MRI could be a next-step option if needed but in most cases, it really isn’t necessary. Surgery isn’t an often picked intervention for cases of lateral hip pain let alone gluteal tendinopathy or trochanteric bursitis so the need for that further depth of information isn’t really there.

As with all imaging clinical correlation of symptoms is goal number one. You aren’t defined by your scan, simply having an enlarged bursa on a scan doesn’t mean you have bursitis. Seeing a physiotherapist should be a necessary next step to correlate your findings with a clinical examination.

Optimising your Management

Hands-on Treatment

Manual therapy is the basis of what we do as physiotherapists and far too often it’s forgotten. High-quality hands-on treatment combined with an individualised exercise program and thorough education should form the basis of what we do. Manual therapy is usually quite important to perform surrounding the area of lateral hip pain. Pushing directly on the irritable tendons and bursae is really just going to make it worse. Working through the hip flexor, quadriceps, gluteals and hip rotators usually forms the basis of where to work. Reducing the muscle tone through these muscles can help to improve function and maximise the benefits of your exercise program.

Reduce Compression

Taking away compressive load is probably the 2nd most important aspect. If you continue to compress the irritable tendons and bursae the symptoms will simply continue to be present and potentially worsen. If you had a bruise you wouldn’t continue to poke it right? So think of this in exactly the same way. Continue to put compressive input to the area, whether that be through stretches or positions that you end up in throughout the day, and you will continue to have symptoms of greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Utilising pain relief should always be an option if you need it, don’t feel like you should push through any symptoms of lateral hip pain that impact your function.

Load Management

Managing load is our 3rd key pillar. If you keep going for your 10km runs or walking up and down hills the area simply doesn’t have time to settle. You have to take a little bit of a step back for your own sake and to allow the body to have a little time to rest, recover, and reset. Managing your load and reducing it doesn’t mean you sit on the couch and re-watch your 5 favourite Netflix shows for 3 weeks and do nothing. It just means taking a step back and monitoring your pain during, after, and the next day and that will give you a good idea. A little bit of soreness and discomfort is ok, but if you are dreading walking those first 10mins in the morning or hating going up and down stairs all morning, you’ve overdone it and take it as a sign from your body to ease back a touch.

Exercise

Unfortunately, prescribed exercises and strengthening is always a thing we physios love giving. The good thing is, there’s plenty of variety of things you can do for gluteal tendinopathy. You still want to work through the tendon loading spectrum to ensure you aren’t overloading the gluteal tendon complex or the bursae. Let’s run through some options for each of the different types of tendon and muscular loading.

Isometric

These are our go-to for early-stage rehabilitation in gluteal tendinopathy. Isometric contractions occur when there is a contraction of the muscle but there’s no movement. Loading the tendon complex and keeping muscle activity going is absolutely vital, use it or lose it somewhat applies here. These contractions should be pretty well painless, a little bit of discomfort I’m ok with but I don’t think it should be painful. You should be aiming for 5 contractions of between 20-45seconds each.

One of the best options I go for is standing and trying to push your feet apart on the ground. It’s really simple and can be done just about anywhere. Another good option can be bridges with a band around the knees to contract the rotation component of the gluteals (mostly the gluteus medius).

Isotonic

The next logical progression is to add movement to the contractions. Isotonic contractions are great for developing strength in our muscles. Staying away from compressive positions early on is name of the game. We need to be working on the gluteus medius and maximus, as well as the other deep rotators, and the abdominal muscles too.

Some great exercise choices could include:

- Bridges

- Crab walk

- Squats

- Step ups – forwards and sideways

- Sit to stand

- Side plank

- Hip abductions in side lying

Utilising bands can be a great way to add intricacies to movements – for example, we can add a band around the knees while doing bridges so that we can produce an isotonic and isometric contraction at the same time and increase the level of difficulty and complexity.

Energy-Storage Loading

The core function of tendons, without developing this capacity for our younger more athletic clients we will be doing them a disservice. Runners and athletes need their tendons to be able to be stiff and compliant to be able to absorb and release force as fast as possible without compensation. Optimising through the lower limb from the Achilles tendon, patella tendon and then up to the gluteal tendons.

Exercise selection is highly dependent upon the athlete, their goals, sport, position, and the way the team plays, among many other things. Nonetheless, some great choices can include:

- Stair running

- Skipping

- Box jumps

- Lateral jumps or hops

- Jumping lunges

- Lateral box jumps

Other types of exercise

I get it, not everyone loves the gym or doing all of these exercises at home. And sometimes the best exercise is the one that gets done, personally, I don’t really enjoy the gym much, I just don’t get hyped to go do 3×10 bicep curls unfortunately. So 2 of the more popular choices are pilates and yoga. These are 2 great options but there are some considerations to keep in mind if you choose them.

Pilates

This is all about using your “core”, some pilates instructors may define “core” differently but Joseph Pilates somewhat defines it as from the bottom of the rib cage down to the pelvic basin including the abdominals, back muscles, pelvic floor, adductors, and gluteals. Developing this core strength is pretty important for fighting gluteal tendinopathy as a lot of clients end up tight through the hip flexors and unable to adequately utilise their gluteals so retraining these abdominal and core muscles can be quite important.

Just keep in mind not to go at it hammer and tongs right from the start. Pilates is all about technique rather than how heavy the resistance is. Make sure you really focus on your form and feeling the muscles working before you progress the resistance. Move up too quickly and you’ll start to adapt and move away from the “optimal technique” and potentially utilise the wrong muscles.

Yoga

It’s awesome, but I’m terrible at it because I have pretty poor flexibility so I should do it more often. Yoga, just like Pilates isn’t at all about resistance and hard heavy work, it’s about technique, flow, and sustaining your core through the movements. Yoga is surprisingly hard and I wish people gave it more credit than what they do, particularly a lot of men out there.

If you have gluteal tendinopathy though, there’s one big thing you need to watch for. Compressive positions such as certain stretches or positions that involve compression of the gluteal tendon complex and bursae aren’t going to make your gluteal tendinopathy happy. Just keep an eye on your symptoms during and after and make note of any new stretches, movements, or positions you work through to try to monitor for any that may be causing issues.

Should I keep exercising while I have it or should I just rest?

100% yes, but monitor your symptoms. Doing nothing is taking the fast track to either recurrence or taking a long time to get back to what you were doing or what you want to do. Gluteal tendinopathy is still a tendon issue and tendons still need some load going through them to stay happy. It could be as little as going out for a short walk on flat terrain or a very easy jog, or simply just your prescribed strengthening program. But avoid the desire to sit at home and do nothing feeling sorry for yourself because it’ll only make life harder in the long run.

How long can it last?

Gluteal tendinopathy can last for a long time, it’s one of the presentations that once it has been there for a long time it can take a while to get 100% better. It takes time and commitment at that point. In cases where you get onto it early, it can take as little as 2-6 weeks to be back doing everything you were doing. In more chronic cases of greater trochanteric pain syndrome, you can look at a few months for a full recovery.

Do I need a corticosteroid injection?

Not in most cases. Without any bursitis findings on a scan, I wouldn’t be racing off for a corticosteroid injection. If you have some trochanteric bursitis on your ultrasound report it can become quite the dilemma. Injections are far from a guarantee of working. In my experience, a lot of it comes down to symptoms and how irritable they are. If clients are reporting a throbbing sensation coupled with significant difficulty sleeping at night I find they are much more likely to respond to injections than others. Ultimately, discuss your options with your GP but always keep in mind that they aren’t guaranteed to work.

What is the long-term outlook?

Pretty good, most cases of gluteal tendinopathy will resolve in time with commitment from your physio and yourself. Tendons can’t be fixed with just hands-on treatment alone, it can’t improve tendon load tolerance but it can make it feel a little bit better. As a physio, I rely on my clients to be consistent with their home exercise program to develop the strength to get over their symptoms in the long term.

Can you prevent it?

I believe so. Stay consistent with an exercise program throughout your life and I really do think that helps you out in preventing it. There are risk factors like being female, getting older, and menopause that isn’t going to help you out but if you control the things you can control you’ll do the best you can. Avoiding sudden spikes in exercise is one of the better preventative pathways. If you’ve suddenly decided you want to lose 25kg maybe don’t start walking 10km every day, gradually work your way up and you’ll be putting yourself in the best position to achieve your goal and stay injury free.

Recent Posts

- Lifting Technique “Never Lift with a Bent Back” – Why Those Words Make me Shudder

- When should I see a Physio?

- Adductor Strains – A Footballers Worst Nightmare

- Hamstring Strains – Frustrating, Recurrent, Our process for how we can help you

- Gluteal Tendinopathy – It’s a Real Pain in the Ass

How can we help?