18 Sep Hamstring Strains – Frustrating, Recurrent, Our process for how we can help you

Strains vs Tears – Same or different things?

Strains and tears are the same, the terms may be interchangeable depending upon who I am talking with, but if someone asks if you have a hamstring strain or a hamstring tear, you could answer either way.

Grades of hamstring injuries

Grading hamstring strains are pretty important for helping to predict a return to play time. Clinical assessment can be a relatively good gauge of determining the grade of muscle injury but if you want to gain further insight imaging is what you will need. MRI is ultimately your best choice but ultrasound can help glean some more information. So let’s dive into a little bit of info on the different grades of muscle injuries and the two main systems that are used.

Traditional grade 1, 2, and 3 system

The system pretty much everyone knows. You do a hamstring strain on the weekend and you see your physio and they diagnose a grade 2 strain. Generally, you’ve got a pretty good idea of what they are talking about and how long you may be out of sport for. Let’s recap what the three grades are.

Grade 1

Generally considered to be a pretty mild muscle injury with some slight stretching of the muscle or very minimal disruption or tearing of muscle fibres. Clinically most clients present with minimal but well-localised pain, full or near full range of motion, slight bruising or swelling depending upon the location, and the athlete may have been able to continue playing after the injury.

Grade 2

These are a little more significant and will correspond with tearing of muscle fibres on imaging – the extent of muscle injury is debated between different researchers but it’s usually between 5 and 50% disruption ranging up to near on a full muscle rupture. Clinically these clients present with more pain than a grade 1 strain and it may be a little less localised, range of motion is usually restricted and painful and they are usually unable to continue playing after the incident.

Grade 3

These are usually pretty significant and are generally considered to be a full muscle rupture and as such have the worst clinical presentation generally. There is a significant range of motion loss and severe and diffuse pain and haemorrhage along with significant loss of function.

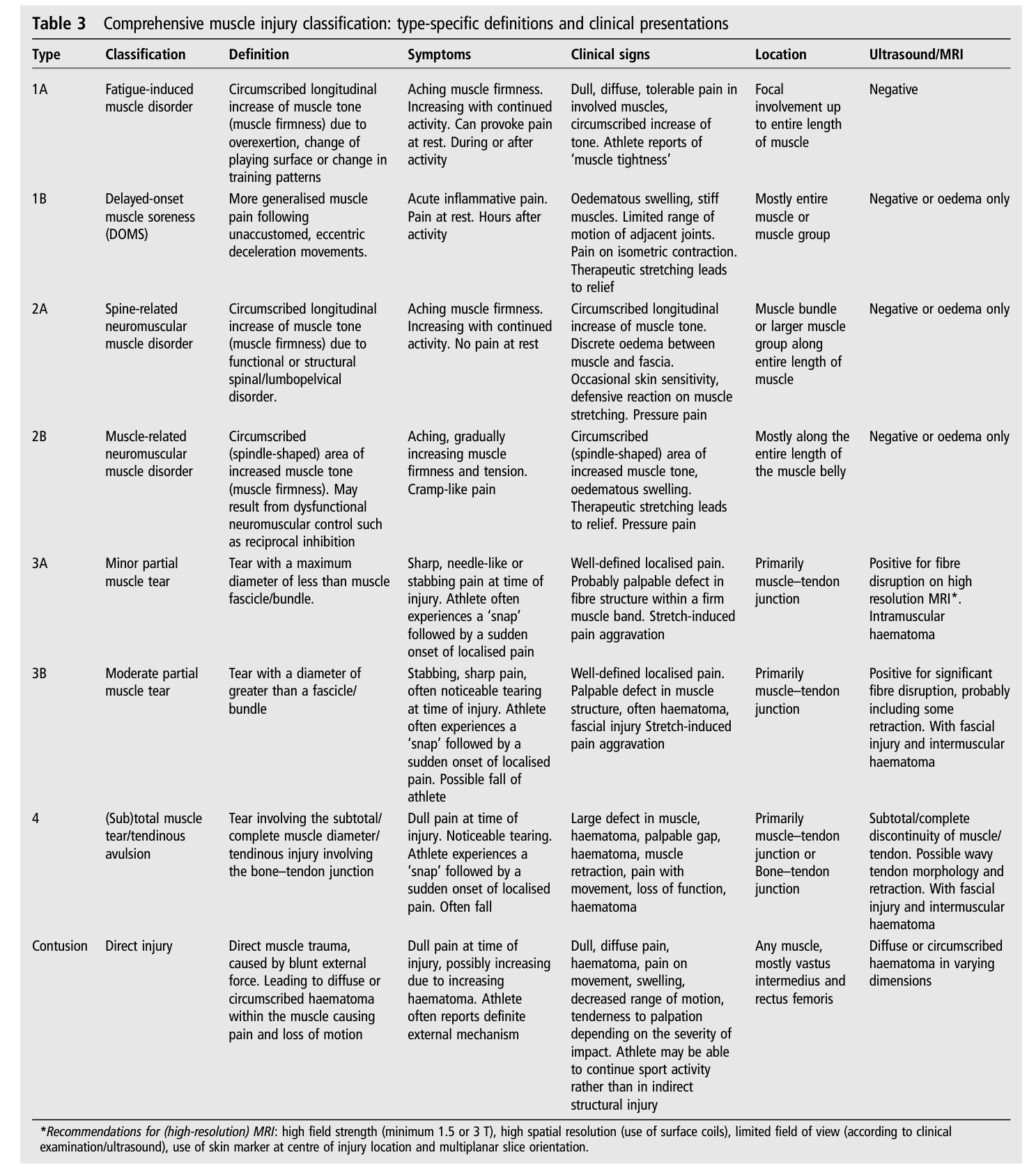

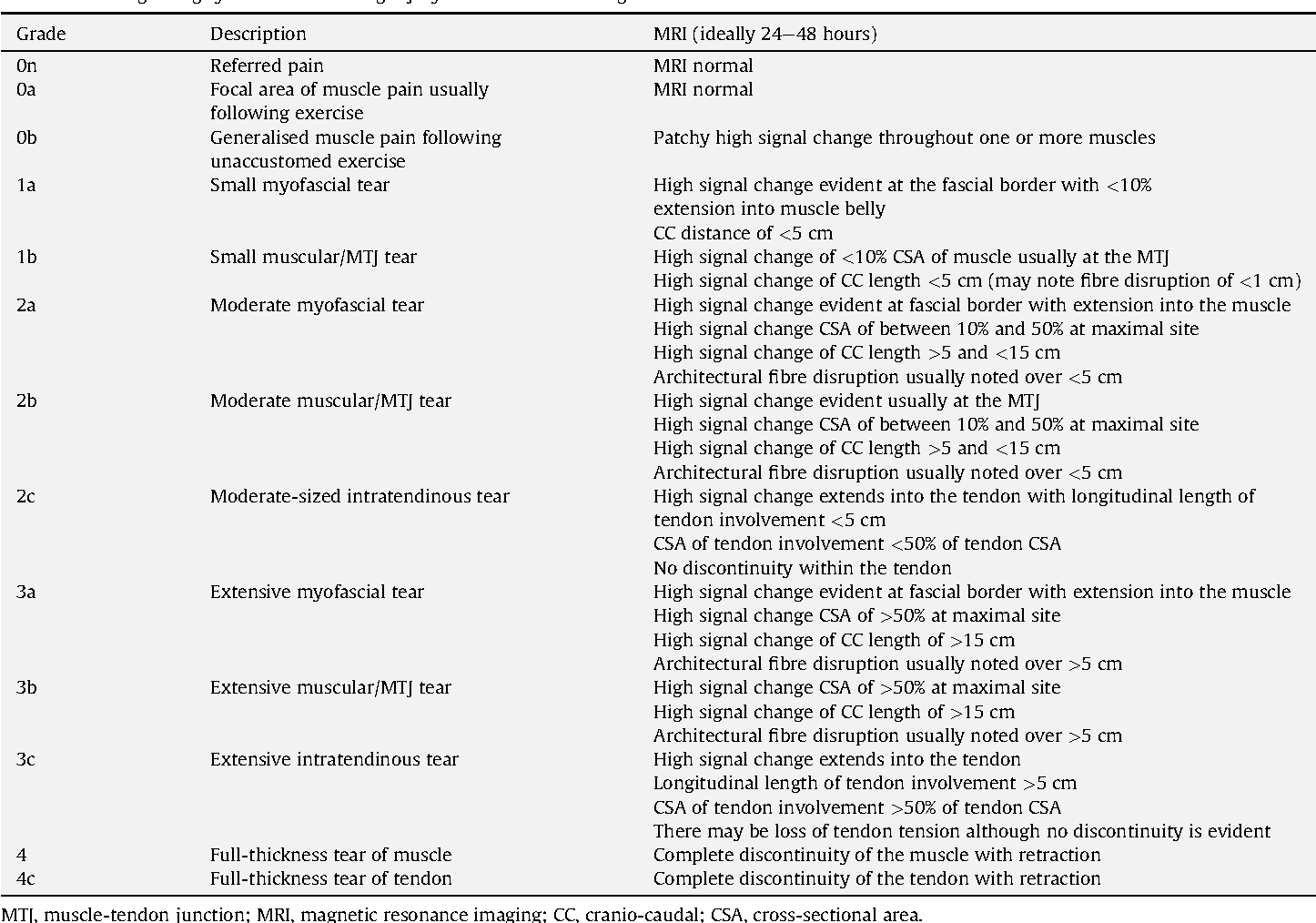

The newer system – British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification System

The old school grade 1, 2, and 3 system is a bit old school and lacks a little bit of depth of information. There’s quite a range of muscle injuries ranging from cramps and DOMS, all the way to muscle and tendon rupture and avulsions, and also including contusion injuries. The old system doesn’t quite account for some of these other injuries. So in 2012, a group of experts gathered in Munich to develop a consensus grading statement for muscle injuries. Unfortunately to truly utilise this system to its best capacity MRI is probably needed, and your physio can help put you on a pathway to get there if you want one. I have attached a copy of the grading system below for you to peruse.

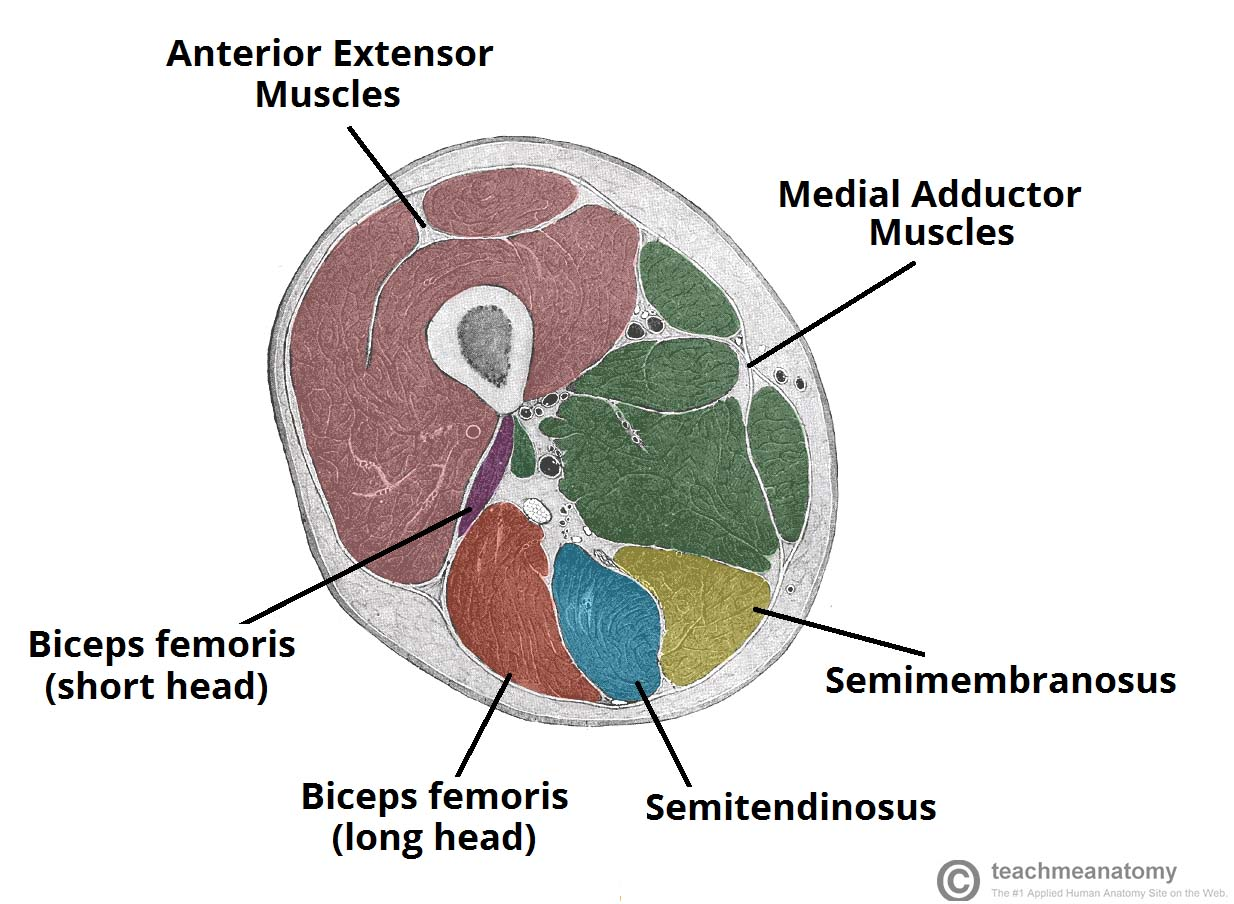

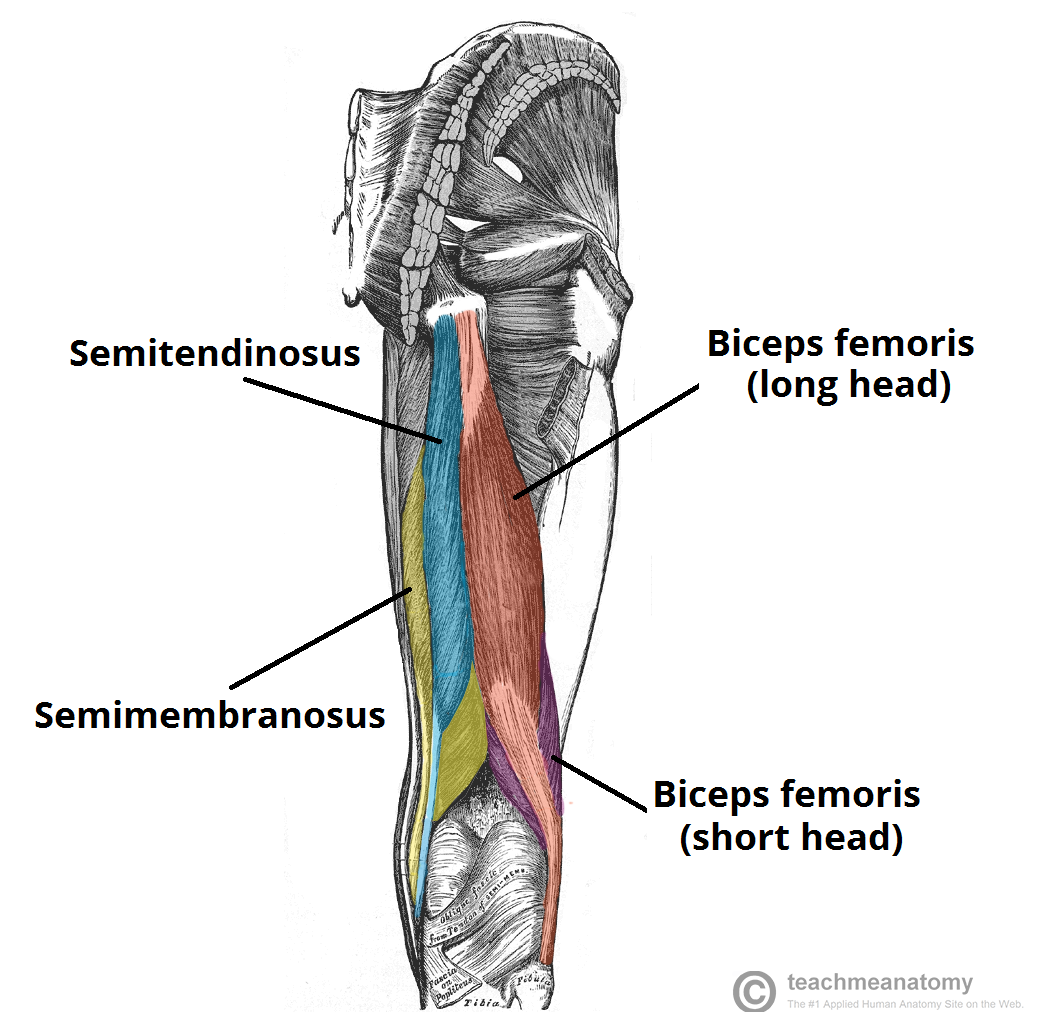

Hamstring anatomy

The hamstring muscles are composed of three separate muscles – biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus. The Biceps femoris consists of two muscle bellies – a short head, and a long head. Let’s separate the three and look at them all in a little more depth.

Biceps Femoris

Muscle origin: short head – linea aspera and lateral supracondylar line of the femur, long head – ischial tuberosity

Muscle insertion: Lateral aspect of the fibular head

Muscle actions:

- Long head: flexes the knee, extends the hip, laterally rotates lower leg when knee slightly flexed, assists in lateral rotation of the thigh when hip extended

- Short head: flexes the knee, laterally rotates lower leg when knee slightly flexed

As you can see the biceps femoris is far from a simple muscle, it has multiple actions and crosses over the knee joint to attach slightly below it allowing it to act on both the hip and the knee. The biceps femoris is probably the most common of the hamstring muscles to get injured as it typically occurs while sprinting under high eccentric loads.

Semimembranosus

Muscle origin: a strong membranous tendon attaches to the upper lateral facet of the ischial tuberosity

Muscle insertion: there are six of them!

- Posteromedial aspect of the tibia

- The MCL

- The oblique popliteal ligament

- The posterior oblique ligament

- The meniscotibial ligament which is part of the medial meniscus

- The popliteus and its aponeurosis

Muscle actions: hip extension, knee flexion, knee internal rotation when the knee is flexed

Whilst the actions of the semimembranosus aren’t as complex as the biceps femoris, its anatomy certainly makes up for it. Semimembranosus is named because of its highly membranous origin structure.

Semitendinosus

Muscle origin: a common tendon origin with the long head of the biceps femoris, from the lower medial facet of the lateral section of the ischial tuberosity, and also from another portion of the ischial tuberosity with its own tendon attachment site

Muscle insertion: upper portion of the medial surface of the tibia

Muscle actions: hip extension, knee flexion, knee internal rotation when the knee is flexed

The semitendinosus relatively sits above the semimembranosus so is a much easier muscle to palpate than the semimembranosus.

What are the common mechanisms for hamstring injuries?

Hamstring injuries pretty commonly occur with two very distinct mechanisms. They form two quite different subgroups of the population and athletes which require different clinical treatment pathways and differing prognoses. The most common is a sprint or running mechanism hamstring strain, and the second is a stretch-style hamstring strain. Let’s dig into them both so you can get a good understanding of each of them.

Sprint mechanism

Sprint mechanism hamstring strains form the majority of the cases I see clinically as well as the research tends to agree with me. So what is it about sprinting that makes it so hard on the hamstrings that it pushes them to failure point?

Stages of Running Cycle

Late Swing Phase

This phase is critical, and generally, it’s the phase of the running cycle where researchers tend to agree the hamstrings are at the greatest risk of injury. Numerous studies have found that this is the point at which the hamstrings display the highest level of muscle activity while also undergoing a significant lengthening activation (eccentric contraction). While this is already quite high, it has been found that biceps femoris activity increases by 67% when running at 100% compared to 80%. Comparatively, semimembranosus and semitendinosus increase by only 37%.

Early Stance Phase

It’s pretty well accepted that a hamstring injury will usually occur in the late swing phase, but we haven’t quite yet shown that it can’t happen in the other phases. The early stance phase is one of the other key areas to look at. Some researchers have been able to find that there appears to be a second peak in hamstring activity, particularly in the biceps femoris, during this phase. Their hypothesis appears to be based on the idea that maximal hip extension and knee flexion torques occur at initial ground contact.

Swing-Stance Transition Period

Should we separate the two or should we just be looking at this as one phase in itself? Essentially large passive torques at the knee and hip during sprinting exist to lengthen the hamstring in both of these two phases. So should they be considered one phase because the joint motions are continuous and the hamstrings are operating to extend the hip and flex the knee throughout the entire phase? If we really haven’t been able to determine which one the injuries always occur at, and they both have significant peaks in biceps femoris muscle activity, and the hamstrings are doing the same thing through the process, maybe it doesn’t make a difference? I think I can say we need further research to help us determine if there is a difference because even with all of the research being done on hamstrings strains and preventing them, we aren’t making much of a dent in it.

Stretch mechanism

Stretch mechanism injuries are much less common than sprint mechanism muscle strains when looking at the hamstring group. In AFL it has been found that approximately 19% of hamstring strains occur during kicking. One of the other common mechanisms in the AFL is picking a ball up off the ground whilst running at full speed, you could conclude that this is a stretch mechanism injury as well given the significant amount of hip flexion in this position. Usually, these sorts of movements occur in movements involving a combination of extreme hip flexion coupled with knee extension. Common mechanisms might include:

- Kicking in AFL

- Picking up a ball off the ground while sprinting

- Dance manoeuvres

- Gymnastics manoeuvres

Typically on MRI, these injuries primarily affect the semimembranosus muscle and typically will occur higher up the muscle. The site of the muscle injury is an important consideration as it often helps to predict the time to return to sport. Often injuries sustained higher up take longer to return to sport.

Often, stretch mechanism hamstring strains take a little bit longer to rehabilitate than sprint mechanism injuries. This is probably due to a combination of a more proximal injury site and a different style of injury mechanism. Whilst they may be a little less painful at the start, don’t take that as a sign that it’s less serious, I’d still recommend getting in to see a physio and get it looked at.

What does a hamstring strain feel like?

Most people who have sustained a hamstring injury could pretty accurately describe the sensation. The most common descriptions usually fall under the pulling, grabbing, tearing, or popping sensations. It’s almost always a sudden sharp pain in the back of the thigh that usually pulls the athlete right back from what they were doing at the time. If they are sprinting for a ball they will almost immediately pull back and struggle to continue.

Some athletes may report an increase in symptoms before a hamstring strain. These could include a sensation of increased fatigue, tiredness, heaviness, or cramping sensations. Signs such as these are a pretty good indication that you are at risk of suffering a pulled hamstring and you should very closely monitor these symptoms before they progress and you suffer an injury. Always remember, the best ability for an athlete to have is availability. You are of no benefit to the team on the physio table rehabbing a hamstring strain.

What does a hamstring strain look like if I’m watching a game?

They are pretty easy to spot, you will almost always see someone grab the back of the thigh after they have sustained a hamstring injury. In cases such as a sprint mechanism, you might be looking for an athlete who leans forwards to accelerate to get a ball just a little too far. Or for a stretch mechanism style injury, you may be looking at something like reaching down for a ball or immediately after kicking a ball again grabbing their hamstring. Almost in every case of a hamstring injury, you will see the athlete grabbing the back of the thigh as an immediate response to the sudden sharp pain they’ve just felt.

What are the risk factors for hamstring injuries?

Previous Hamstring Injury

The biggest risk factor of all, for pretty much any injury out there, is a previous injury to the same area. Just having sustained a previous hamstring strain increases my risk of a future one, let alone if you did a poor job of rehabbing it before returning to sport. This risk factor is pretty obviously non-modifiable, so once you’ve had one you should be doing a hamstring strength maintenance program to ensure you are staying strong and long in your hamstrings.

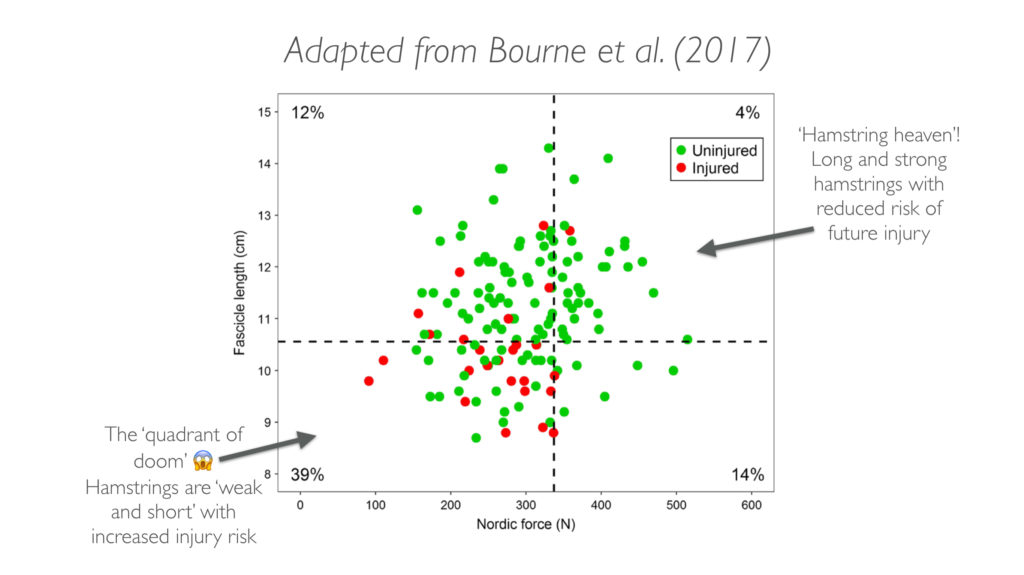

Weakness

Onto the modifiable factors, weakness is number 1. If you have weak hamstrings, particularly a lack of eccentric strength you might find yourself in a bit of trouble in the future. Below we will introduce you to the “Quadrant of Doom”, but essentially you will find there is a strong correlation between people with weak and short hamstrings and an increased risk of sustaining a hamstring injury. Professional sporting teams worldwide regularly perform targeted strengthening of the hamstrings to purely improve strength to reduce their risk profile.

Reduced Fascicle Length

Tight hamstrings are number 2, reduced fascicle length of the muscle fibres in the hamstring muscle bellies is the other key factor. Static stretching and eccentric biased exercises are two great ways of helping out here. Without the adequate length of fascicles, and the capacity of the hamstrings to work in the ranges that they are often asked to work in either as field-based athletes or as dancers or gymnasts, the risk of injury is going to jump up. If I can’t get my hamstrings to fully lengthen out just doing a stretch, how can I expect them to do it on game day, over and over again? Eventually, something will reach breaking point and you will feel that all too familiar pulling sensation at the back of your thigh.

“Quadrant of Doom”

It’s pretty aptly named going off of the graph below. The Nordic force measure is determined by utilising a specialised piece of equipment that measures the maximum force output during a Nordic curl. Whereas the fascicle length was determined through measures nobody can do clinically. What I want you to see is the number of red circles in the bottom left in comparison to every other quadrant. There are A LOT more in that quadrant than the others. The takeaway you should be taking from this graph is long and strong is best for preventing hamstring injuries.

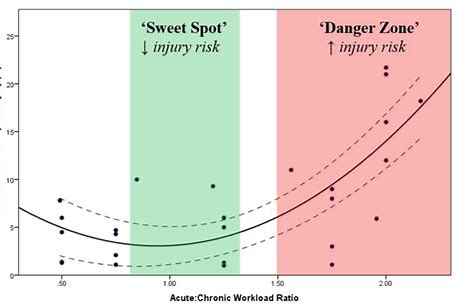

Training Load

Being ready to perform what you are going to be asked to do on the pitch, court, dancefloor or whatever environment you’ll be in, being physically prepared for it is key. If you haven’t been training and you just decide to turn up on the day, you may as well flip a coin if you will get injured in my mind. When looking particularly at something like a hamstring strain the biggest predictor when looking at training load is how much sprint work have you been doing. Sprinting takes a lot of work from the hamstrings, repeated accelerations, deceleration, change of directions, and just generally working around the pitch means fatigue takes its toll. If you haven’t been doing your sprint training as an extra from your regular training work, increase your dosage of sprinting to help bulletproof those hamstrings.

Old Age

It would be good if we were all invincible and could run around like 18-year-olds for the rest of our lives. Alas, getting older is a part of life, and getting old is an inevitable risk factor for suffering a hamstring injury. Once you hit 25 your risk increases by about 2.5x, but 25 isn’t that old I hear you all saying. It is to your hamstrings though! So you better have built some long and strong hamstrings by the time you are hitting your mid 20’s. Some other research has found that for every year you get older your risk increases by about 1.3x completely independent from any previous history of a hamstring injury.

How can I prevent a hamstring injury?

Strength and length are arguably the two most important controllable factors for hamstring injuries. There’s nothing we can do about getting older or previous hamstring injuries until we learn time travel. Eccentric-biased based exercises such as Nordics appear to have a significant benefit towards reducing hamstring injury rates. Eccentric exercises are not only great at building strength but they are also fantastic at improving muscle fascicle length.

The other factor I would say is highly controllable is sprint loads. Sprinting has been found to have the highest level of hamstring muscle activity. So not only is it great for building strong hamstrings, but it provides dosage for maintaining and increasing your training load. For example, at the soccer club I work at, the GPS data has shown that players sprint on average of 1500m per game. If they haven’t developed the tolerance to sprinting for that distance, the likelihood of them breaking down mid-game is significantly higher.

Thirdly, developing strength and control above your hamstrings is key. If you don’t have strong glutes and a strong core your ability to take bumps and hits and maintain control is much lower. Hamstring injuries aren’t just about the hamstring muscle. Everything has to work together for an athlete to be able to perform at their peak.

What makes a hamstring injury worse?

Playing on

As with just about any injury you can sustain, playing through a hamstring strain is far from advice I would give to someone. As part of the risk: reward payoff I consider there is a huge amount of risk and unless it’s the grand final there is almost always not much reward for playing through it other than looking tough in front of your mates. Often athletes want to continue to “help the team out”, but you may be better served to allow a fully fit player to take your place, as well as not having to rehab for as long following your injury.

Alcohol

Alcohol acts as a vasodilator, which means that it causes blood vessels to relax and widen. Vasodilation isn’t bad. But if I’ve just sustained an injury that is going to create an inflammatory cascade, it’s probably not the best thing to induce. You might enjoy a post-game beer, and almost everyone does, but after a hamstring injury put the alcohol down and opt for water if you want to enhance your recovery time.

How soon after my injury should I get it assessed?

If you have a team physio, get it assessed straight away. Differentially diagnosing between a true hamstring strain and potentially sciatic pain is a critical element as they are two completely different presentations and treatment pathways. If you have sustained a hamstring injury and don’t have a team physio I’d probably recommend getting in and seeing someone either one or two days later. Getting an accurate hands-on assessment and diagnosis and progressing onto an exercise program will reduce your recovery time, maximise your rehabilitation, and reduce your risk of re-injury on return to sport. Research has shown that beginning an eccentric-based exercise program earlier has resulted in a faster return to sports times and improved measures such as strength and fascicle length in the hamstring muscles.

Diagnosis and Assessment

Subjective Examination

This part of the examination for a client who has just suffered a hamstring strain is vitally important. Let’s delve into a few of the key discussion points I’ll discuss with my clients.

Mechanism of injury

Determining the mechanism of injury and how and when it happened are crucially important. Not only is this a key factor in assisting us to determine a prognosis (stretch vs sprint mechanism), but helps us determine what potential other risk factors we may be looking out for. If you mention that you had an increase in fatigue and heaviness in your hamstring muscles before the injury that will be something that a clinician should be looking at objectively.

Previous injury history

No duh, this is asked for pretty much anything right? The incredibly important question though, is we’ve got to know if you have had a hamstring injury before and if you have how many. Determining how strong this risk factor is is so important for clinicians. Then we will need to discuss your rehabilitation if you did any. This will often revolve around what treatment did you receive and to what extent did your exercise rehabilitation prepare you for returning to sport.

Sporting calendar

We obviously will want to know what sport you play and what position you play. But one of the most common questions I find gets missed for clinicians managing sporting clients is where is the sporting calendar at. If you have finals starting in 3 weeks that’s very different to it being the middle of the pre-season games schedule. Not necessarily that this will change what we will do and how we will treat it, but getting an understanding of the lay of the land helps put the injury into perspective and understand the risk: reward ratio.

Objective Examination

Objective and clinical testing should simply be used to rule in and rule out other potential diagnoses. Outside of that, we are assessing how significant is the hamstring strain.

Palpation

Touching and feeling is one of the best skills physios have, palpation is a key part of the assessment of a hamstring strain. It allows us to see how sensitive the area surrounding the strain is to touch, how big the area of tenderness is, as well as feel for changes in muscle tone in the muscles surrounding the area.

Isometric Testing

Specific isolated muscle contractions are one of the optimal ways to rule in or rule out a hamstring strain. For a hamstring you will be wanting to perform isolated knee flexion contractions, you could perform an isolated hip extension contraction but I don’t find many clinicians opting for it. The other benefit of knee flexion contractions is that I can work the hamstring through varying ranges of knee extension and hip flexion thereby allowing me to put greater stress on different parts of the hamstring muscles, or simply ask the hamstring to produce more force.

Muscle Length Testing

Stretch is often the third component of muscle injury assessment, an acute hamstring strain isn’t going to like knee extension, or in some cases, combined hip flexion and knee extension. The client must stay relaxed through the movements as they are designed to be completely passive in the way that the clinician moves your leg and you stay relaxed.

Once I have a positive test for palpation, isolated muscle contraction, and pain on muscle stretch, I’m pretty confident that I will be dealing with a hamstring strain.

Neurodynamics

Probably the most common differential diagnosis needed for hamstring injuries is whether it is muscular or whether it is the sciatic nerve. Sciatic nerve pain can present somewhat similarly. I recall seeing a client a few years ago with hamstring pain who had been getting managed as a hamstring strain but on neurodynamic testing we were able to recreate her symptoms perfectly. Treatment of the sciatic nerve pathway led to the near-complete resolution of symptoms within the session. Think of neurodynamic testing as trying to stretch a garden hose. As I put different parts of the hose on tension, if there’s an area of the hose that is caught under a car tyre, or someone is standing on it, the hose isn’t going to move any further. Common sites for nerve restriction could include the lower back, through the gluteal muscles, or restrictions through the hamstrings themselves. Your physio should be capable of performing the different movements and positions to differentiate between these.

Functional Assessment

Getting up and doing something should be a part of pretty much any physio assessment. How much you do is completely dependent on how irritable your symptoms are, but we want to have a good understanding of what you are and aren’t able to do. Common functional assessments physios could perform for someone with a hamstring injury could include:

- Squat or single-leg squat

- Walking

- Stairs

- Jogging

- Hopping

- Jump squats

- Lunges

- Arabesque

Ultimately, that list isn’t exhaustive, and a lot of what you perform will come down to what you do as an individual either in day-to-day life or in your sport.

Imaging

To get a scan or not is one of the more common questions clients who has just had a hamstring injury will ask us. Ultimately I don’t think they are necessary unless there is something that seems a bit out of the ordinary – either the initial response to treatment isn’t what is expected, the pain isn’t settling as it should, or the level of symptoms doesn’t match the mechanism of injury. The two options for imaging are either ultrasound or MRI, so let’s dig into both of them a little bit.

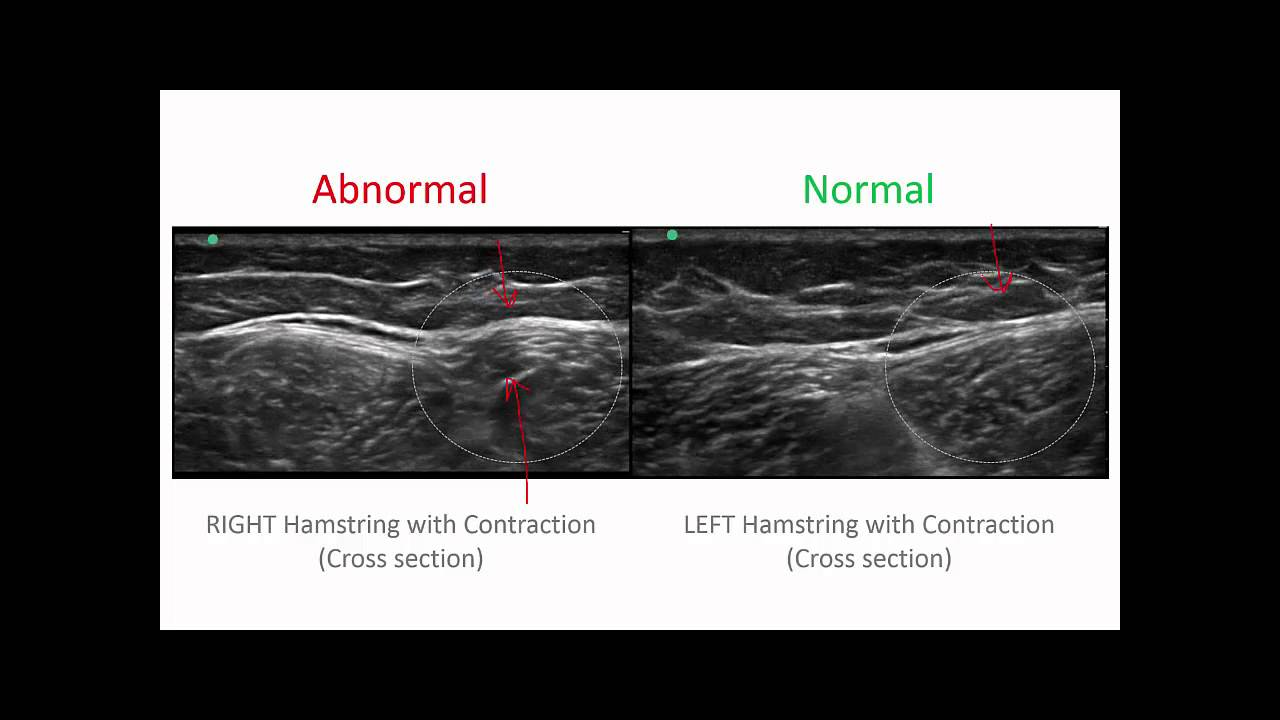

Ultrasound

Ultrasound can be useful for assessing the hamstring muscles and tendon structures. It is sufficient for assessing for a strain of the muscle or a tendon tear and can report on potential haematoma or swelling processes. It isn’t quite as powerful as MRI but for most clients, it is going to be sufficient.

MRI

This is probably your best imaging choice should you feel the need to go for imaging and are happy to pay the cost for an MRI. It reveals significant information about the tear and helps to delineate whether there is intramuscular tendon involvement which can prolong recovery time. MRI is much more powerful and can reveal a greater depth of information than ultrasound can. Clinically, MRI doesn’t reveal much more information from a prognostic perspective, so I wouldn’t be recommending anyone with a hamstring injury go racing off for an MRI. I think it is best utilised in cases that don’t seem to match what should be happening and probably start considering it around that 1-2 week mark.

Management

Hands-on Treatment

The skill every physio should be good at, hands-on treatment is vital to optimising your recovery following a hamstring injury. Good quality manual therapy can put you on the fast track to getting better quicker and improving your functional capacity. Some basics need to be crossed off the list, the most common hands-on techniques I’ll be doing with my clients include:

- Hip flexor and quadricep release

- Gluteal release

- Lower back release

- Lumbar spine mobilisations

- Calf release

- Light hamstring release or trigger point treatment

I would imagine most physios running around in the sports physio world are doing pretty similar. There may be a few changes here and there depending on the clinical presentation or if something seems out of the ordinary but this is a pretty good starting spot for most clinicians. As you progress through your rehab there may be some more specific things you may have to be working on, sciatic nerve issues aren’t necessarily uncommon so some neural pathway work as it goes through the hamstring muscles can provide some great relief and functional improvement.

Hands-on treatment is all about improving function and enabling you to perform your exercise program, at no point is hands-on treatment a replacement for your exercise program. Physio is all about working as a team to optimise your function and performance, without a structured exercise program returning to sport without a significant risk of re-injury is significantly harder.

Strengthening

You have to nail this if you want to maximise your recovery and minimise your recovery time. Getting compliance with an exercise program is probably one of the hardest tasks physios face, I get it they aren’t fun, and it often isn’t that exciting, but it works, trust me.

Isometric

Static holds might have to be your starting point of hamstring loading depending on how irritable your symptoms are. Isometric exercises can be a great way to load a muscle but not set off any significant symptoms. With these sorts of exercises you are wanting to work on building time under tension, you would rather work below your maximum capacity, but build the time you are holding it for.

Example isometric exercises could include:

- Bridges

- Heel digs

- Hamstring curl

For a starting point, you could work on a basis of 5x20sec holds and then try to increase your time from there, or you could be looking to progress towards isotonic work.

Isotonic

We want to try to get to this work as soon as possible. Isotonic work is going to help get our hamstrings working through differing ranges and increasing workloads at different points in the range. We need to be focusing on both concentric work as well as eccentric work (so much so that it has its section just down below!). Concentric work is great for us being able to continue to develop our strength and power capacity, but the downside is that concentric contractions have been found to reduce fascicle length. And if you remember from earlier, we want LONG and strong hamstrings. So balancing it with a stretching and mobility program, as well as eccentric-only exercises is what we need to be doing. Also drawing from something we discussed early is the fact that the hamstrings act over two joints, the hip and the knee. So we can’t just go to the gym and do some hamstring curls and expect to be bulletproof. We need to be working on the hip extension component, and the knee flexion component of the muscle fibres.

Some great exercises to choose from can include:

- Hamstring curls – seated and prone

- Bridges

- Hip thrusters

- Swiss ball hamstring curls

- Nordics

- Deadlifts

- Good Mornings

- Hamstring eccentric sliders

Plyometrics

Everyone knows I love my plyometrics and they are such an integral part of developing a robust athlete who’s ready to return to sport. Progressing tendon and muscular stiffness during patterns that can lead towards running progressions is what we need to be looking at. Early progressions we can introduce can include skipping, a great calf-strengthening exercise and fantastic for developing Achilles tendon stiffness. Squat jumps can be another great one where we can work through depth ranges as well as increase speed. Then we look at progressing on towards hopping on the spot, hopping forwards, or hopping over hurdles. Or even a progression such as scissor jumps or hurdle hops with trunk flexion. All of these options are fantastic choices to help develop your plyometric capacity and increase your hamstring tolerance to reduce your risk of a hamstring injury.

Eccentrics

These are all the rage in the world of hamstring rehabilitation and in the prevention of suffering a hamstring injury. As we discussed above, a lot of the mechanisms of hamstring strains occur when the muscle is at a long length and under a high load, particularly looking at the sprint mechanisms, under a lot of eccentric loads. So the development of eccentric strength naturally makes sense. If we don’t develop the capacity for it to do what it most likely did when it got injured have we completed rehabilitation? I would argue we haven’t. There are multitudes of articles published by Anthony Shields who originally developed the concept showing its benefits in prevention and rehabilitation paradigms. Not only that, there has been recent research that has shown that the adoption of early lengthening-based exercises working into an acceptable level of pain has been shown to improve times to return to sport, and improve clinical measures upon clearance for return to sport. So eccentrics might be a little new to some people, but they work. They are hugely beneficial to bulletproofing those hamstring muscles and you should continue doing them for the rest of your sporting career regardless of whether you have a history of hamstring injury or not.

Exercising the rest of the body

You may have sustained a hamstring injury, but you can’t neglect the rest of your body just because your hamstring is a bit sore. Keeping the rest of you in tip-top shape is your best idea. Working on your calves, glutes, core and hip flexors is key to being ready to return to sport when your hamstring is. If you neglect everything else while you rehab your hamstring injury you will simply increase your risk of injuring a different part of your body when you come back. Some great example exercises can include:

- Calf raises

- Front planks

- Side planks

- Crab walks

- Palloff press

Mobility and Stretches

Maintaining your flexibility is the next key pillar of your rehabilitation. We need to consider both muscular flexibility, joint mobility, and neural system mobility. All three of these areas will affect your potential outcome from rehabilitation. Muscular mobility is a key indicator for both return to sport and a potential risk factor for your hamstring re-injury. Joint mobility feeds into and works with muscular mobility, stiff joints may result in tight muscles, and tight muscles may cause tight hips. Keep them both happy, and you’ll be happy. Neural mobility is usually the one people don’t know about. Restriction of the mobility of neural pathways can cause a lot of issues and may often present as either pain at the back of your thigh, or tightness and pulling sensation slightly similar to that of a muscle stretch. There are a few key tests that physios perform to help us differentiate between true muscular restriction and restriction of neural mobility.

Examples of common stretches and mobility exercises:

- Knee-to-wall stretch

- Knee-to-wall ankle joint mobilisation

- Hip flexor stretch

- Quadriceps stretch

- Gluteal stretches

- Lower back stretches

- Hamstring stretches

- Sciatic nerve gliders/sliders

Returning to Running

Getting back to running is one of the first big milestones in hamstring rehabilitation. The earlier you can return to running the quicker you can get back to sport which is what everyone is working towards here. If you look at the EPL or any professional sport they are wanting their athletes to maintain running patterns as early as possible even if it means making modifications. Common changes they might make include reducing stride length or reducing running speed. These two things will take a lot of load away from the hamstrings allowing us to maintain running technique and keeping the motor pattern going. Ideally, you should be able to be performing isotonic hamstring exercises as well as have near full range of motion before looking at returning to running.

Returning to Training

Training is the next big thing to check off of the list. What I would want you to complete entirely depends upon what sport you play and what it involves but in most cases we are going to be wanting you to have likely done 1 week of running work before training to allow time for the hamstrings to adapt, build up the speed work, and ensure you are going to respond positively to training and not take 3 steps back. We must take a graded approach back in rather than just go full steam ahead of the first session back, remember to train smarter not harder.

Returning to Play

The end goal as always is to be back to playing competitive games again, it’s what every athlete wants to do. Before returning to play you need to have completed AT LEAST 1 full training session but ideally 2 to complete for most teams a full training week. You need to have equal strength on both sides and the full range of motion with no compensations. A common measure to use for football (soccer) players is a 100deg active straight leg raise as this has been determined as the range most football players require to not increase their risk of injury. At the end of the day, you have to have completed a full session to get my tick of approval, show me that you can go out and do what you will need to do in a game otherwise I will be nervously awaiting to hear whether you survived the game without reinjuring.

What is the longer-term outlook?

For those of you out there with a long history of hamstring strains and potentially poor rehabilitation, maybe say a few prayers. Seriously though – get into your strengthening, particularly the eccentric work (Nordics for example). You already have a history of injury and potentially age risk factors in play so minimise the risk from the others and keep those hamstrings long and strong, and keep your sprint loads up.

For the people who have just suffered their first hamstring strain, the outlook can be pretty good, if you do a good job of rehabilitation and don’t try to cut corners and race back to playing too early. You will get out of this what you put in. A hamstring strain has an incredible ability to hold an athlete back from their peak performance if they go back too early or haven’t done the work.

Unfortunately, sometimes injuries happen. I remember a client I worked with years ago who had a significant history of hamstring injuries, he performed near on all of the rehabilitation you could do plus extra and performed a regular and ongoing injury prevention program, but he just couldn’t shake them being an issue. It was disappointing because he was a fantastic footballer. Avoid becoming him, do your prevention work even if you haven’t had an injury yet, and if you have had one make sure you do everything you can to prevent a recurrent hamstring injury.

How long does it take to recover?

For most cases, you are looking at the 2-6 week range for returning to competitive sport. Lower-level strains will typically be at that 2-week point, not often can athletes recover within a week from a true muscular injury. In the case of a contusion, or a cramp, it’s certainly possible, but once there has been a strain it’s much less likely without a significant risk of injury. A grade 2 strain will usually be within the 3-5 week range, and a higher grade injury or an injury involving the intramuscular tendon could be more towards the 6-8 week range and potentially extend out longer in very particular cases. Some injuries such as a hamstring tendon tear or rupture, or a tendon avulsion will potentially require an orthopaedic surgeon’s opinion as to whether surgery is or isn’t required. Obviously, in these cases, recovery time is going to be much longer extending out in the months timelines rather than weeks but largely depends upon the injury and the surgical techniques used.

Can my hamstring get injured again?

Most definitely, don’t consider it like a broken bone where it’s unlikely that you will break that bone again. Soft tissue injuries are notorious for re-injury. Risk factors such as a lack of strength and a lack of muscle length are indicators that proper rehabilitation hasn’t been completed. You can usually pretty easily spot an athlete who hasn’t completed their rehab, they are robbed of their athleticism, speed, and change of pace. Put in the work, get the results, and put yourself in the best position to not have the “Will my hamstring go today” question swirling around in the back of your head during a game.

Recent Posts

- Lifting Technique “Never Lift with a Bent Back” – Why Those Words Make me Shudder

- When should I see a Physio?

- Adductor Strains – A Footballers Worst Nightmare

- Hamstring Strains – Frustrating, Recurrent, Our process for how we can help you

- Gluteal Tendinopathy – It’s a Real Pain in the Ass

How can we help?