23 Sep Adductor Strains – A Footballers Worst Nightmare

Adductor tendinopathy vs Adductor Strain

These two are commonly mixed up but they are quite distinct from each other. The major key difference is that tendinopathy will develop over a long period of time just sitting there in the background. They often won’t cause you to stop playing your sport but will cause a loss of performance and athleticism. In football (soccer) it’s often found as one of the lowest time loss injuries but causes the most functional difficulties for athletes. A groin strain though will happen in an instant and you’ll know about it. It may occur during a change of direction movement, when being tackled, or when kicking a ball, but you will feel that familiar “pop” or “pulling” sensation indicative of a muscle strain.

How do I know if I’ve strained my groin?

As I mentioned above, the all too familiar “pulling” or “pop” sensation is usually your first identifier. Secondly, you’ll typically be able to identify a moment that it occurred, you might not have this huge moment of pain that makes you fall to the ground, but identifying a certain pass, or a certain tackle it occurred in is pretty common. In mild cases, you may still be able to run and potentially sprint in a straight line but it will be changes of direction and turning that will give you issues. This eccentric loading and short sharp contractions of the adductors is where you will lose the capacity to perform, straight line running fortunately doesn’t involve that. Looking particularly at soccer players here, kicking and passing the ball, particularly crossing or switching the ball will usually give you significant difficulties and you will find a loss of power.

How serious is a groin strain?

They can get pretty serious, significant injuries such as a rupture are obviously ones that you want to deal with sooner rather than later. But even mild muscle strains such as a grade 1 are relatively significant for athletes. The adductors are important muscles that assist in stabilisation around the knee joint and contribute stability and force production to change of direction and kicking movements. If you are an athlete seeking to perform at your peak, losing performance on movements such as those, you simply cannot afford that loss of capacity. So get it seen to and get working on some rehab and strength work to allow you to produce that power again.

Who commonly gets groin strains?

Having worked with soccer teams for the last 5 years and going into my 6th year I would have to say dealing with groin pain is one of the most common presentations I see. Adductor tendinopathy is probably more common for me to treat rather than an adductor strain though. Groin strains and groin pain are definitely much more common in younger athletes such as late teens to early to mid-20s, adductor tendinopathy I would say I see more in mid-20s to early 30s athletes. It’s not overly common that I see it in older athletes, the reason for this I’m not too sure, whether it is just the lack of “explosiveness” in the older age groups that is a potential reason. AFL, rugby league, and rugby union are the other common sports that groin pain can be a common presentation, though it isn’t as commonly seen as it is in soccer.

What does a groin strain feel like?

Location of symptoms

Acute groin strains are often quite a localised pain sensation more towards the muscle belly than the tendinous section more towards the pubic symphysis. The muscle bellies of the adductors sit in the middle third to the upper third of the inner thigh. Often clients will be able to pinpoint their pain location to a circle with just a few centimetres in diameter.

Common pain descriptors

The pain of an acute groin strain is often described in a few common ways:

- Grabbing

- Pulling

- Shooting

- Popping

- Sharp

It’s not often that a client will describe an acute adductor muscle injury as being a dull, achy, or diffuse sensation, they are more typically reserved for injuries that have developed over a longer period of time such as an overuse injury like tendinopathy.

What does adductor tendinopathy feel like?

Location of symptoms

Adductor tendon concerns usually present with pain quite high up the adductors more situated around the tendons and potentially referring down into the adductor muscles themselves. Often the pain will slowly develop over a period of weeks to months and often be worse initially during exercise, then potentially settling down during, and then increasing again afterwards. Most of the potential symptoms that people may feel in the adductor muscle section will often be better described as stiffness, tightness, or generalised achiness rather than a specific sharper type of pain. Some clients with longer-standing adductor tendon issues may report pain travelling across the pubic symphysis and radiating to the opposite adductor tendon complex as well. While not uncommon, it is more than likely related to a long history of symptoms.

Common pain descriptors

Tendon concerns are very different to those often related to a groin strain. They are slow developers, they sit in the background for weeks or months at a time with people not taking too much notice of them. Often clients will describe sensations such as:

- Achy

- Throbby

- Bruised

What makes an adductor strain worse?

Playing through it

As with pretty much any injury, playing through a groin strain will ultimately make it worse, adductor tendinopathy is a slightly different answer though. An adductor strain involves an acute injury to the muscle and/or tendon tissue, this acute injury causes an inflammatory cascade. If you continue to play you will simply increase the cascade and make the effects after the game much worse. Adductor tendinopathy on the other hand is a different beast. Because tendons just deal with the load and there is no structural muscle or tendon injury playing through symptoms is possible if they are lower-level symptoms. I utilise a traffic light system, on an adductor squeeze test if you have pain between 0 and 3/10 you can play, between 4 and 6/10 you can modify your training, anything 7/10 or above and you need to take some time off. At the end of the day, speak with your physio and discuss the pros and cons of training and playing and come to a shared decision about your best pathway forwards.

Alcohol

Liquid courage doesn’t do much for helping out with muscle injuries, particularly acute injuries like muscle strains. Alcohol works as a vasodilator, which means that it increases with the diameter of blood vessels, not so great if you have an inflammatory issue going on. Avoid the post-game beers if you’ve just suffered an injury, you might feel a little better at the time, but it may delay your recovery and you definitely won’t be feeling that good tomorrow (either due to a hangover or post-injury soreness).

Stretching

Personal opinion here, and it could be a little scandalous I get it. But often I find people do not respond well to stretching groin issues. Everyone always seems to want to do it and it always amazes me that people think that stretching is the sole answer to fixing the issue. Strengthening should form the core basis of your exercise program and often I find people respond better to eccentric-based exercises for muscle lengthening coupled with hands-on treatment such as massage and trigger point release to reduce muscle tone than they do stretches.

When should I see someone for groin pain?

ASAP, not only for an accurate diagnosis and assessment to rule out other potential causes of hip pain but mostly to get started on an individualised exercise and strengthening program. Unfortunately, groin pain is far from simple from a diagnostic perspective. The earlier you can get an assessment the fewer confounding factors there will be for your physio on an assessment which makes life easier for everyone. If you delay getting your groin pain seen to you can potentially begin to see adaptations happening around the hip and groin area involving the hip flexors, glutes, lower back, and hamstrings, this makes management a little more complex and convoluted so may increase your time to return to sport.

What are the risk factors for groin pain?

Previous injury to the adductors

Previous injury is always going to be a risk factor for just about any injury and the adductors are no different. Put simply, if you’ve had an adductor muscle or tendon injury previously, you should be doing everything you can (hint injury prevention program) to prevent it. Adductor injury prevention programs don’t have to be big, some strength training, some sprint loads, and some mobility and flexibility work and you are on your way there to a pretty good program already.

Weakness of the adductors

Far and away the biggest risk factor groin is either groin pain or a groin strain, and it always blows my mind how common it is to find this being a problem in athletes. Soccer players are the most common culprits and they arguably use their adductors more than just about any other sport or athlete out there. Weakness of the adductors is clinically assessed utilising a handheld dynamometer to assess for force output, it can be assessed one leg at a time or as a squeeze test between the two legs. Weakness of the adductor muscles results in reduced force output, increased fatigue, and reduced performance, once an athlete reaches both local muscular fatigue, as well as cardiovascular and mental fatigue in a match the risk of sustaining a groin strain increases.

Training load

As per pretty much any other lower limb injury we’ve discussed, and arguably any injury in general, training load always plays a factor. If you haven’t clicked on to that yet I don’t know what else to say really. When looking at the adductors, similarly to hamstrings, sprint loads, decelerations, and change of direction loads are the big three training load metrics that you need to be keeping up. Topping these up can be as simple as doing an agility course twice per week to keep the engine running nicely. You could also theorise, that if you were performing an ongoing injury prevention program and stopped doing it suddenly mid-season, that could also be perceived as a reduction in training load specifically to the adductor muscles

Lower range of hip abduction

For field-based sports having the requisite range of motion to be able to perform your sport-specific tasks is necessary. For sports such as soccer or AFL where you can require significant amounts of hip adduction range of motion to perform movements such as kicking, reaching for a ball, tackling another player, or a contact-related knock that moves your hip through abduction range, if you don’t have the range of motion and strength to control that range you may find yourself in some trouble. Whilst there isn’t the same body of research that there is for hamstring injuries and the “Quadrant of Doom” we spoke about in our blog on hamstring injuries I suspect there would be a similar correlation of long and strong adductors performing best when looking at injury rates.

Lower levels of sport-specific training

Turns out training isn’t just good for getting better at your sport. Sport-specific work is not only good for developing a well-rounded athlete but it exposes you to what you will have to do on game day. Put simply, if you haven’t prepared well to go and do what you are about to do, you are putting your body at greater risk of failure. Training and warm-ups should be seen as preparing my body for what I want it to do, far too often players just go through the motions. If you want to lower your risk of sustaining an acute injury like a groin strain during a change of direction motion specific to soccer, guess what, you better do it and expose your body to it so it can adapt and get stronger doing it.

Higher level of play

As you begin to play at higher levels in any sport the play gets faster, the collisions harder, and the stresses on your body increase proportionately. An increased risk of groin pain or a groin strain is most likely due to these increased stresses you are encountering. As you change direction faster and faster the load placed upon the adductors eccentrically builds up. The other aspect is the increase in training load if your body isn’t accustomed to it.

Relevant Anatomy

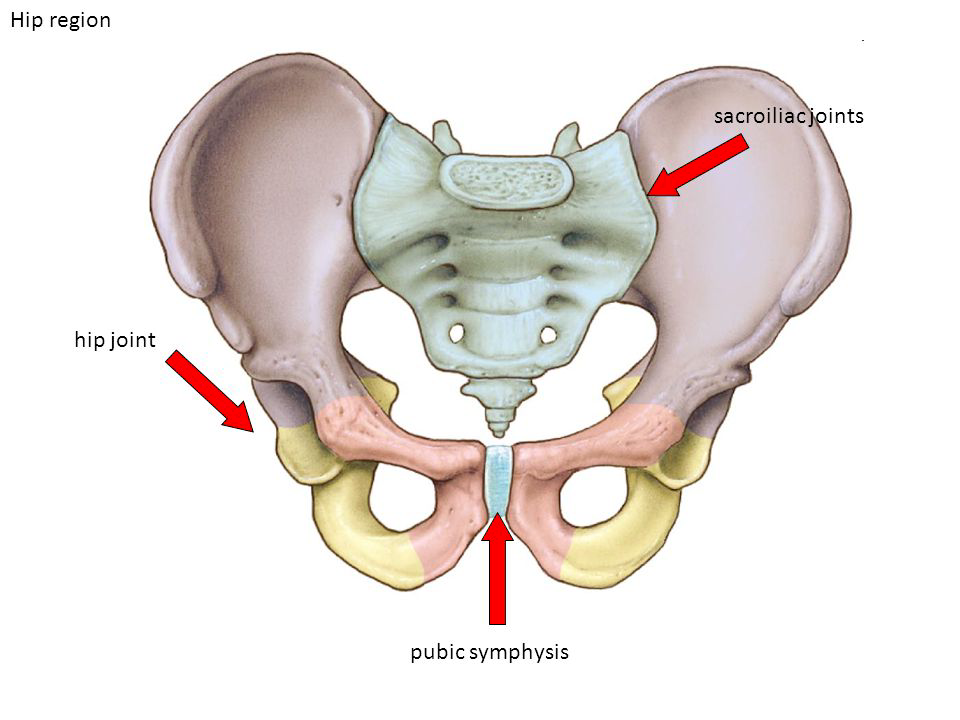

Pubic symphysis

The pubic symphysis sits at the front right between your two pelvic bones. Its job is to essentially hold your two pelvic bones together, aside from during pregnancy, the joint really doesn’t move a lot, because it’s not designed to. There are two main components to the joint, first is the fibrocartilage disc made of mostly type 1 collagen. The second is a coating of hyaline cartilage made of mostly type 2 collagen and it covers the end of the pelvic bones with the fibrocartilage disc sitting between the two.

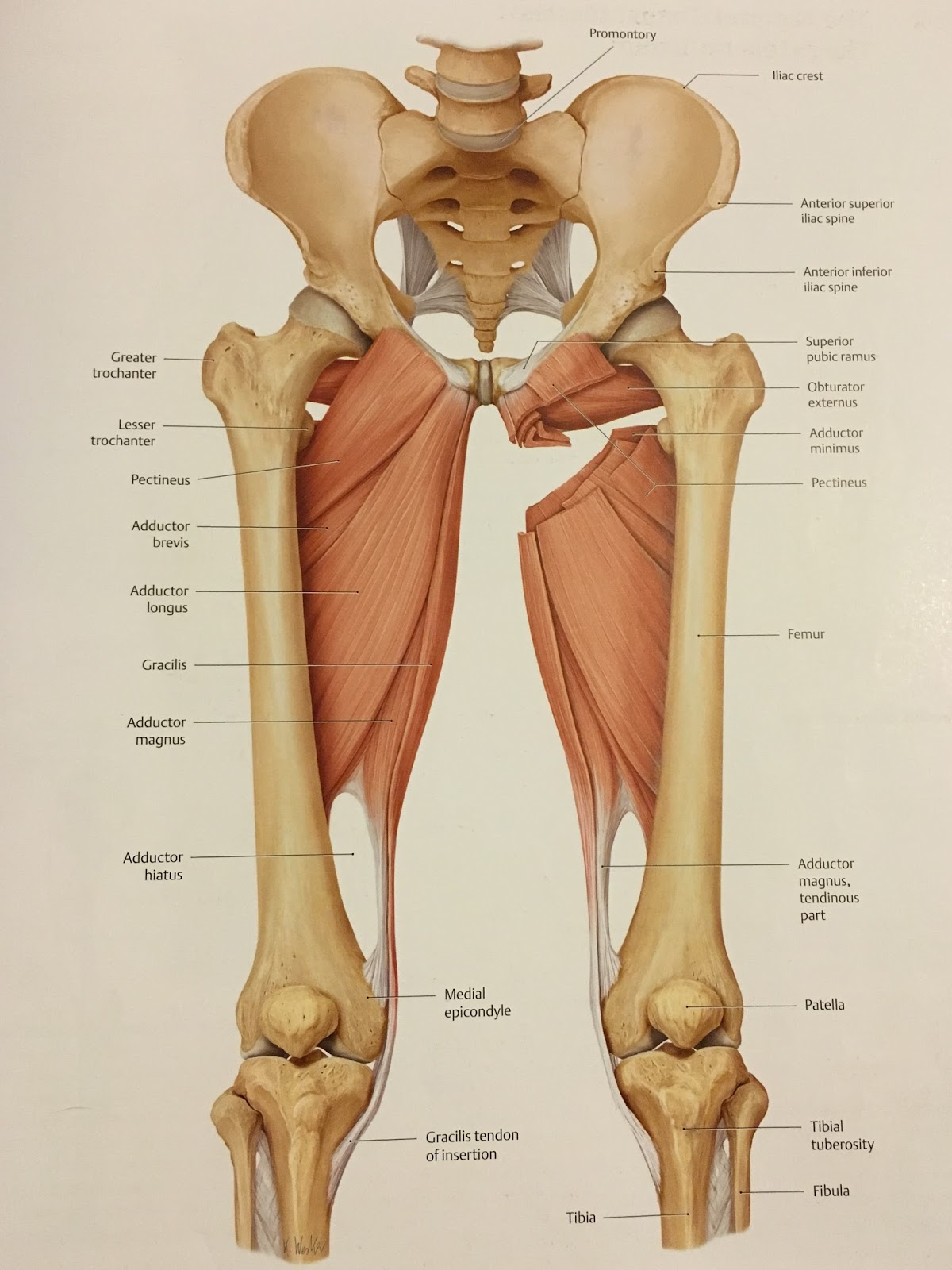

Adductor muscles

The adductor muscle group is made up of 5 main muscles which we will break down below. They all have slightly different actions but all together mostly work to produce an adductive force.

Adductor longus

Origin: Body of pubis, inferior to pubic crest and lateral to the pubic symphysis

Insertion: Middle third of linea aspera of the femur (medial lip)

Action Hip joint: Thigh flexion, Thigh adduction, Thigh external rotation; Pelvis stabilization

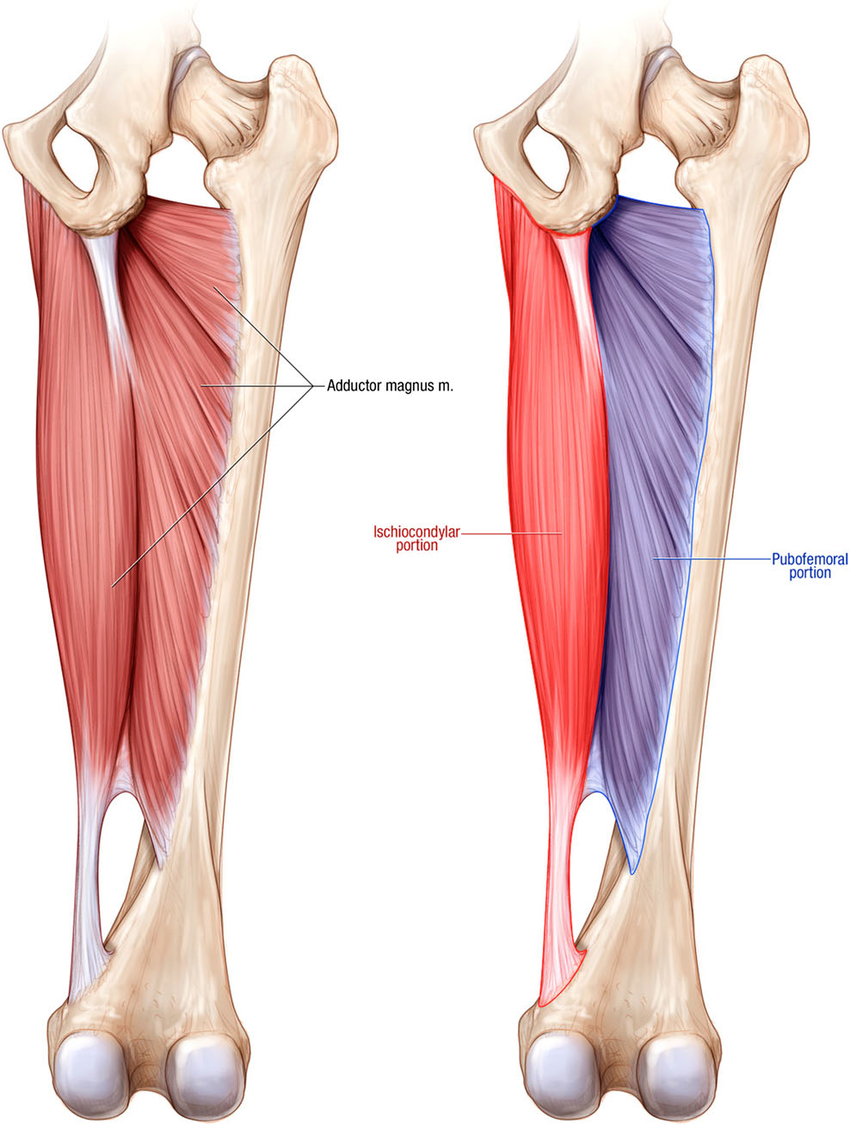

Adductor Magnus

Origin:

Adductor part: Inferior pubic ramus, ischial ramus

Ischiocondylar part: Ischial tuberosity

Insertion:

Adductor part: Gluteal tuberosity, linea aspera (medial lip), medial supracondylar line

Ischiocondylar part: Adductor tubercle of femur

Action:

Adductor part:

Hip joint – Thigh flexion, thigh adduction, thigh external rotation

Hamstring part:

Hip joint – Thigh extension, thigh internal rotation

Entire muscle: Pelvis stabilization

The adductor magnus is one of the cooler adductor muscles because it somewhat acts as a 2-in-1 (I’m male I love 2-in-1 things like combined shampoo and conditioner, it just makes life easier). The two portions are the ischiocondylar and pubofemoral parts and both have quite distinct actions from each other.

Adductor Brevis

Origin: Anterior body of pubis, inferior pubic ramus

Insertion: Linea aspera of femur (medial lip)

Action: Hip joint: thigh flexion, thigh adduction, thigh external rotation; pelvis stabilization

Gracilis

Origin: Anterior body of pubis, inferior pubic ramus, ischial ramus

Insertion: Medial surface of the proximal tibia (via pes anserinus)

Actions:

Hip joint: Thigh flexion, thigh adduction;

Knee joint: leg flexion, leg internal rotation

Pectineus

Origin: Superior pubic ramus (pectineal line of the pubis)

Insertion: Pectineal line of the femur, linea aspera of femur

Action: Hip joint: Thigh flexion, thigh adduction, thigh external rotation, thigh internal rotation; pelvis stabilization

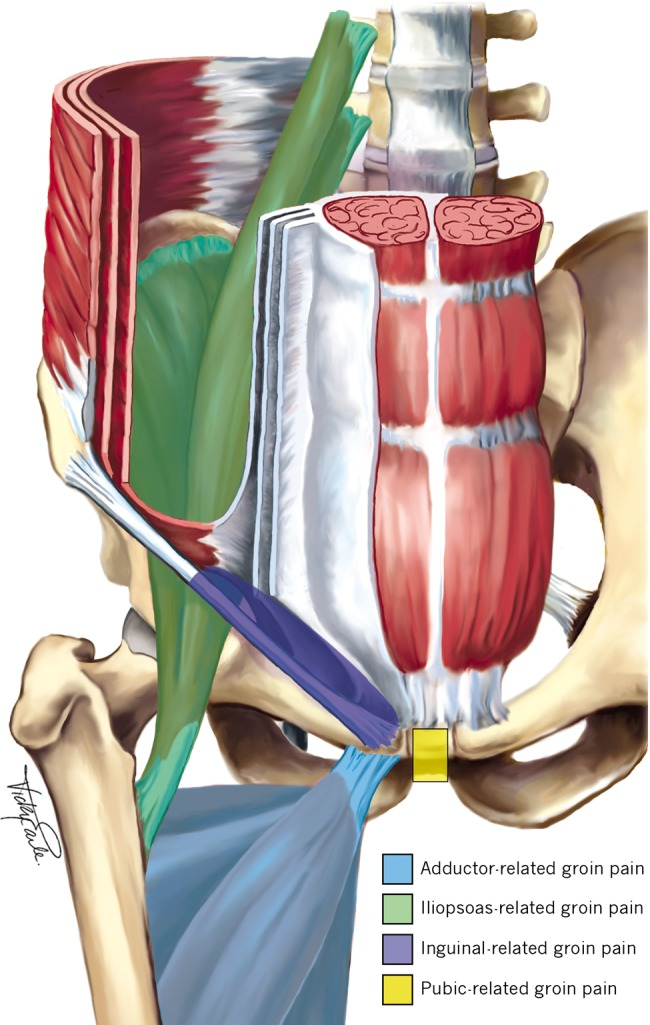

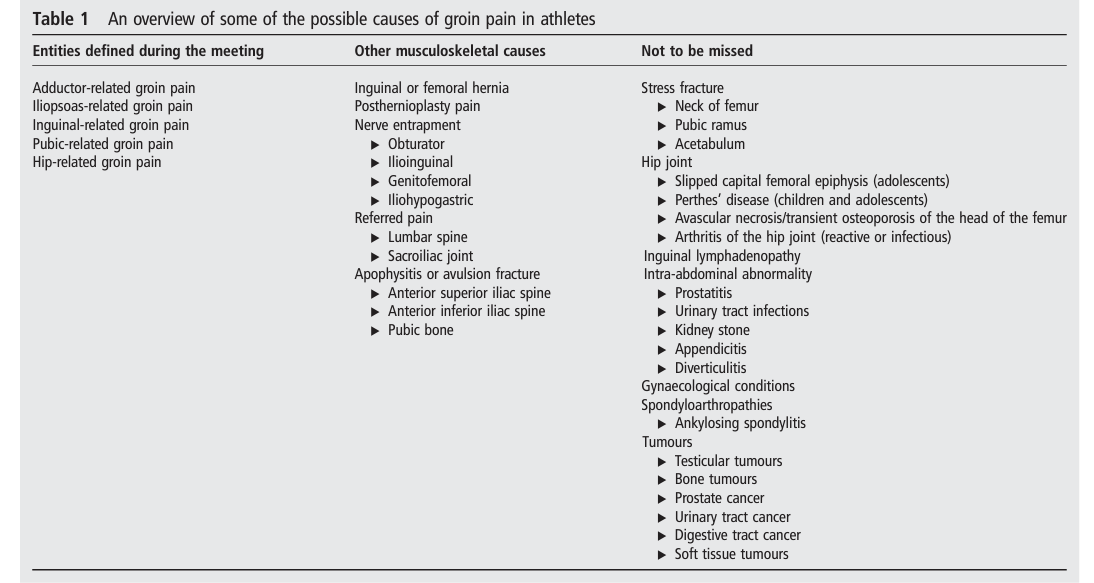

Differential Diagnosis

Hip related pain

By far probably the most debated and most researched over the last 5 years within the physio realm. A large proportion of the assessment for hip joint-related groin pain should be based upon subjective assessment as the specific tests related to the hip joint have good sensitivity but poor specificity (good to pick up potential cases, but not great at determining that structure specifically). If there is suspicion of a structural cause of hip joint-related groin pain further imaging could potentially be warranted.

Subjective Assessment:

- Pain onset

- Nature and location of symptoms

- Mechanical symptoms such as clicking, catching, giving way, or locking

Objective Assessment:

- Hip joint passive range of motion testing

- FABER

- FADIR

Pubic symphysis-related pain

Pubic symphysis pain is a little easier to diagnose than hip joint-related groin pain so life gets easier from here on out. This presentation typically has pain located at or right around the pubic symphysis and has direct pain to palpation. There isn’t any direct muscular resistance of length tests utilised to diagnose this subgroup of pain.

Hip flexor-related pain

Hip flexor pain is again relatively simple to work with, what we are looking for as clinicians are direct pain on palpation of the iliopsoas as our main diagnostic criteria. The presence of this subgroup becomes more likely if there is pain on hip flexion contraction and/or pain on stretch as well.

Inguinal canal-related pain

Inguinal canal pain and a hernia are two different diagnoses here so don’t get the two mixed up. This subgroup occurs when there is a pain in the inguinal canal region and tenderness to palpation but there isn’t a hernia palpable. This diagnosis becomes much more likely if the pain is recreated on testing of the abdominals or on a Valsalva, cough, or sneeze.

Adductor-related groin pain

Obviously, we are going to delve into this a little bit more in-depth a little later on in this blog, but we are looking for a recreation of symptoms on palpation of the adductors and on as isometric adduction contraction.

Why does the hip feel like the Bermuda Triangle sometimes?

The hip and groin area is complex, differential diagnosis can be difficult because a lot of the common areas that produce symptoms refer symptoms elsewhere that cross over with other areas. Subjective assessment is still key, but a thorough objective assessment is arguably just as if not more important to get an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan. That is where the Doha Agreement came in. It defined what the 5 areas of hip and groin-related pain were, clearly laid out how to differentially diagnose them with clinical tests and how to classify them to make assessment and diagnosis clearer for clinicians and clients.

Assessment and Diagnosis

Subjective Assessment

History of symptoms

The history of symptoms is arguably one of the most important subjective assessments for any injury but it is crucial for groin pain. First, we will need to determine whether we are looking at an acute muscle strain of the adductor muscles, or whether we are looking at a longer-term concern such as a tendinopathy. We’ll also need to discuss whether your symptoms have changed over time or if it is more of a chronic case. Discussing your symptoms and what they feel like will be the second topic. Delving into the pain sensations and intensity of those symptoms is imperative. It gives us insight into what structures may be at play as well as how irritable your symptoms are. This could include what activities aggravate or settle your symptoms, for example, turning a corner may aggravate symptoms and it settles within 2 min, but if you kick a ball it may take 10 min to settle. Getting a gauge of this gives us a great deal of insight as to how much load your adductor muscle and tendon complex is happy to accept at this stage.

Previous history of groin pain

Having dealt with soccer teams for the last few years I don’t think I have encountered many players who haven’t reported any previous history of groin pain. It’s unfortunately one of the most common complaints in this population. Regardless of whether you are a soccer player though, determining your history of groin pain is critical. Someone who has had 8 episodes of groin pain or groin strains in the past may be managed a little differently than someone who has just had a first-time groin strain. As part of this, if you have had a history of a prior groin strain, we will discuss in detail what your treatment entailed – did it involve hands-on treatment and if so what type of work, as well as what exercise rehabilitation did you do – how long for, what exercises, how committed and consistent were you. All of this information is needed to help develop a full clinical picture prior to our objective clinical assessment.

Sporting history and current activity

Your previous history as an athlete gives us a good indication of where you SHOULD be as an athlete looking at strength and your general loading capacity. If you have been a soccer player for the last 10 years I would have different expectations compared to someone who hasn’t played soccer for 15 years.

Athletes always want to get back to sport ASAP, I totally get it, as a runner and former basketball and soccer player I always want to be out there doing something. But sometimes people have packed sporting calendars – particularly teenagers these days. Sometimes we have to pick and choose what is our biggest priority. If a teenager has school soccer, soccer club training, games each weekend, and then has a representative carnival in 3 weeks’ time, they may have to choose and something may have to give because, in some cases of groin pain, we simply cannot do everything to the level you want to perform at. And often I find clients want to perform at their peak even if it means giving something up than performing at 75% for a longer period of time.

Objective Assessment

Palpation

With so many structures referring to different areas around the hip and the groin region, a physio’s capacity to utilise their hands to touch and feel for muscle tone through the adductor muscle bellies, the hip flexors, hamstrings, and other muscles is so important. I feel some physios are shying away from using hands-on assessment and treatment techniques which I feel is quite sad. Not only can we feel what is happening with the muscles but we can assess for pain. Specific palpation of bony landmarks, tendon attachment sites, muscle bellies, or ligaments should be the bread and butter of any physio out there. With regards to groin pain, there are specific palpation sites that the Doha Agreement recommends to assist in the differential diagnosis. Specifically for the adductors, it is recommended that we palpate the tendon attachment. Differential diagnosis on palpation often includes palpating the inguinal canal, the pubic symphysis, and the hip flexor. These are specific sites and a well-trained physio should be both capable of finding them and determining whether the outcome of palpation is clinically relevant.

Isometric Muscle Tests

An isolated assessment of muscles is one of the key assessments following an adductor strain. An isolated contraction of the adductors recreating your groin pain is one of the best clinical assessments with good specificity and sensitivity. Specifically assessing one muscular contraction force without any movement allows us to reduce any potential confounding factors such as joint movement, ligament stability, and nerve involvement, mostly because there is no movement with these contractions. What we are looking for clinically is the replication of your symptoms, if they aren’t your symptoms, then the test is largely seen as a negative test. For differential diagnosis, the other common test utilised is an isolated contraction of the hip flexor.

Muscle Length Tests

Muscle length tests are the 3rd factor common for the diagnosis of muscle injuries. When looking at the adductors and cases of groin pain we are wanting to assess the client’s range of abduction (taking the leg away from the body). As with all of our other clinical tests we are looking for the reproduction of your pain, specifically the pain that you feel during daily life or when it is aggravated. Other sensations around the groin or hip area should be noted but it is largely a negative test if your symptoms aren’t reproduced.

The other test that you can perform in combination with this is an adduction contraction while the leg is in an abducted position, this can put the adductor muscles under a greater amount of strain and may potentially pick up a positive test that may not have been found with the legs in neutral.

For other differential diagnoses, a hip flexor muscle length test is most commonly performed. This test is called the Thomas Test and can allow for the assessment of the quadriceps, hip flexors, adductors, and lateral hip region.

Ruling out other hip and groin concerns

As we’ve already covered, differential diagnosis around the hip can be quite a complex process. We need to differentiate between the hip flexor, adductors, pubic symphysis, and inguinal canal. All of this is before we consider whether there could be a lumbar spine neural referral, a hernia, an abdominal issue, or a hamstring issue. The hip and groin are incredibly difficult. A concise and well-conducted objective assessment with key objective tests picked following the subjective assessment to drill down into the root cause of your issues is what is needed. Ruling in and ruling out potential diagnoses as you go. Palpation of structures, specific isometric testing procedures and muscle length assessments must all be completed at a minimum to hone in on a specific potential cause of symptoms. Other potential tests such as assessment of neurodynamics and assessment of the lumbar spine may also be necessary depending upon the findings in a subjective assessment.

Functional Assessment

An assessment of the capacity of a person to move and load in both forwards and backwards as well as laterally and diagonally forms another key portion of the objective assessment. Walking and running are two of the most common tests that we will perform but may branch out into my dynamic and plyometric assessments including:

- Walking lunges

- Side lunges

- Squat jumps

- Hopping on spot

- Hopping forwards or sideways

- Back and forth side hopping

- Diagonal lunges both forwards and backwards

- Single leg balance

- Change of direction technique

Whilst this list is far from exhaustive I hope it gives you an idea of what a thorough functional assessment of the hip and groin may look like for an athlete.

Imaging

Utilising imaging for groin pain should always be done with caution, once we are dealing with athletes we may have some findings that are completely normal and may not be related to symptoms. Soccer players in particular may have findings on an ultrasound that are asymptomatic findings.

Ultrasound

Often the first step people will utilise is to assess the adductor and groin region. Ultrasound has been found to be adequate for determining the presence of local tendons or muscular changes. This is usually the best pathway for most people who either have an acute groin strain or have a longer-term history of groin pain. If you are someone who may potentially have hip joint-related pain as well you may be better served to undergo an MRI.

MRI

MRI is a little bit better than ultrasound in most aspects, we get a little bit better detail of the muscular changes but it often allows us to assess for potential hip or pelvic bony/joint abnormalities such as a labral tear within the hip joint. I don’t find many clients require the intervention level of an MRI so don’t feel that you need to go racing off to get one ASAP, discuss it with your physio and your GP and have a diagnosis in mind that you are looking for. The most common mistake people make is going for an MRI to “see what’s there” and then letting that take over their clinical decision-making.

Treatment Pathway

Hands-on Treatment

A physios bread and butter, we should be one of the best professionals at performing this but so often I hear from clients that they haven’t received it. In most cases of groin pain or an acute adductor strain, hands-on treatment is so crucial. There are some pretty common techniques that I tend to use. Adductor muscle release on both the affected and unaffected side is probably the most common work that I do, taking the muscle tone out seems to do wonders for reducing some of the symptoms people report. Working through the hip flexors and hamstrings are probably the two other areas I find commonly give clients some good relief from symptoms. They probably tend to be more of a compensatory mechanism where we are able to free up through someone’s stride and allow some more freedom through the front of the hip joint.

Exercise

Exercise as always should form the basis and the foundation of your rehabilitation. Without it, you will simply not be able to develop the load tolerance to continue to progress towards returning to sport.

Isometric

As always, the easiest level of loading is isometric holds, we’ve covered the basics of these in plenty of other posts but in essence, we are looking at contractions that don’t involve movement of the limb or joint. For adductors, we can perform something as simple as getting a soccer ball and placing it between our ankles and working on a 5×20-25sec hold basis working at around a 65-75% intensity. I don’t find often we need to work really hard on these contractions, it is more about building that tolerance to the adductor muscle and tendon complex. If between the ankles is too irritable you can just move the ball up to placing it between your knees, and if need bending the knee to take further stress off. This just reduces the lever length placed upon the adductors and should reduce your symptoms while performing the exercise. It is better to get the intensity and time under tension than it is to work at a level that produces higher levels of symptoms but you can’t get the quality exercise in.

Isotonic

Progressing to concentric and eccentric contractions is the next best step. Working through range is so vital for an adductor strain because it works through a wide range of movement in a variety of different planes depending upon the sport you play. For a football player, there is a huge range of movement, velocity, and power or finesse needed to play the sport at a high level. Simply performing the basics won’t develop an adductor that is ready to go out and perform everything you will ask it do. It’s necessary to work through different ranges of movement and speeds to prepare yourself. Therabands are great assistance for working through this, you can move your body in different positions to simulate different kicking motions. The other great benefit of therabands is it allows you to utilise your whole body. Remember that kicking doesn’t produce power just from the legs, the trunk and arms play a crucial role too. Working on and developing that motor pattern through the kinetic chain ensures that you are ready to return to sport. Potential exercises in this stage could include:

- Side-lying adduction

- Adduction against theraband

- Hip adduction machine at the gym

- Kicking with theraband

Plyometrics

Sometimes the good thing about adductor injuries can be that maintaining plyometric capacity is a little easier. Because the adductors work a lot on lateral movements, often we are able to keep clients working on their plyometric work in straight lines with minimal to no symptom production. This means we can usually continue working on squat jumps, hopping, skipping, and potentially running or sprinting depending upon symptoms all in a straight line. The huge benefit of this is that it means we can maintain training load work and we just need to branch into lateral and multi-directional work as we progress.

Flexibility and Mobility

I don’t typically prescribe adductor stretches too much in cases of groin pain and probably less often in cases of groin strains. I often don’t find clients need it that often. Where clients often need to be doing flexibility work is the surrounding musculature, often the hip flexors, quadriceps, gluteals, and hamstrings are the common culprits of tightness. If you can maintain as much mobility through these areas whilst working on your adductor strength you will often have improved upon the baseline you came in at from your injury. The goal following rehabilitation should always be to make you a more robust athlete upon returning to sport.

Exercising the rest of the body

Fortunately, with groin pain, we can continue to work most of the rest of the body. We really want to be working on the core, glutes, hamstrings, and calves. If we can keep all of these areas strong and functioning well the return to sport process will become much easier, it will simply become a matter of building up your running tolerance, sprint loads, training time, and game readiness from a physical and mental perspective. Common exercises you can still continue performing include:

- Front and side planks

- Crab walks

- Bridges

- Squats

- Single-leg calf raises

- Deadlifts – weight dependent

- Palloff press

- Crunches

- Oblique crunches

- Back extensions

Return to Training

Getting back into training is a godsend for most athletes, whether you are an individual athlete such as a tennis player or a team athlete such as a soccer, AFL or rugby player. Getting out there and doing what you love is why you have done all of this rehab work in the first place. It can be tempting to get back out there and just go H.A.M. Usually that is the worst option though unless you have delayed returning to sport until you are absolutely 100% perfect which often isn’t the best pathway anyway. Building back into training is a process, often it starts with small work such as completing the warm-up, some fitness work and some passing and technical work. Then you can progress the next week to including game drills in a small-sided situation before the next week adding in full gameplay scenarios to ensure you are completely ready to return to sport. As with any other injury, completion of at least 1 full training session, but ideally 2, before returning to competitive gameplay is my minimum requirement outside of clinical testing measures.

Return to Sport

This is always the end goal for any athlete, returning to the sport they love hopefully a more robust athlete than what they were when they got injured. Recovering from a groin strain often isn’t a fun time but they are far from the worst injury to suffer. The most important factor I find to consider is how well can an athlete perform cutting and changing directions, I find this is where athletes who aren’t ready to play get exposed. Clinical measures I often use include:

- Adductor squeeze test <2/10 pain

- Full-range hip abduction

- Normal Thomas Test

- Able to complete a full training session with gameplay

- Able to perform agility courses such as Illinois Agility Test

Making sure these tests can be passed as well as an athlete passing the “eye test” will usually tell you that an athlete is ready to come back and play. How that process is managed is very team dependent. Most coaches I have worked with in soccer would rather a player come back and start. Often I recommend that most players will usually be able to confidently play 60+ mins if they have completed a thorough rehabilitation before returning to competitive play. But as always, monitor your symptoms during the game and if things are progressing and you feel it tightening up or stiffening up, always err on the side of caution to prevent re-injury in the early stages of returning to competitive play.

What is the long-term outlook after a groin strain?

Generally pretty good, a groin strain doesn’t have to the notorious reputation for re-injury that its neighbour the hamstrings do. Most of the risk lies with developing ongoing groin pain if you haven’t developed adequate strength during your rehabilitation and haven’t continued on with an injury prevention program. I get it, injury prevention isn’t sexy, it ain’t fun, and nobody ever gets jealous of the player doing their injury prevention work before every training session. But I’ll tell you now, they always get jealous when they are on the physio table and you are out there training. Remember, the best ability is availability.

Can I prevent groin pain?

Prevention of a groin strain or ongoing groin pain pretty much always comes down to strength and training load management. Strength is pretty much the number one key factor in the development of ongoing groin pain and is a predictor of the risk of an acute adductor strain. I honestly believe that any AFL, rugby union, rugby league, and particularly every soccer team should be completing routine adductor strengthening work as part of their ongoing injury prevention program. Leaving this out simply increases my risk profile of getting either niggling groin pain throughout the year, or risking soft tissue injuries. Managing your training load for multi-directional running and change of direction work along with ball work and kicking is the other key factor, if you decide that you want to take 2 or 3 weeks off from agility work to make sure your players are “fresh”, maybe think again. It would be a better strategy to keep them ticking over and maybe reduce their load slightly, but stopping it would be asinine.

I have persistent groin pain, does that mean I have a groin strain?

Persistent groin pain and an acute groin strain are two completely different presentations. You could develop ongoing groin pain following an acute strain, that’s 100% possible and I find it is one of the common stories people tell as part of the history of their chronic groin pain. Whilst these are two different presentations, the management isn’t entirely different. In both cases, we are wanting to increase the load tolerance of the adductors. There may be a few other factors to address in chronic groin pain such as working around the core and optimising the way you move as well as some extra hands-on work. But the core foundation of developing greater load tolerance to the adductors is the same.

Recent Posts

- Lifting Technique “Never Lift with a Bent Back” – Why Those Words Make me Shudder

- When should I see a Physio?

- Adductor Strains – A Footballers Worst Nightmare

- Hamstring Strains – Frustrating, Recurrent, Our process for how we can help you

- Gluteal Tendinopathy – It’s a Real Pain in the Ass

How Can We Help?