24 Aug Plantar Fasciitis – How to make it suck a little bit less

What is plantar fasciitis?

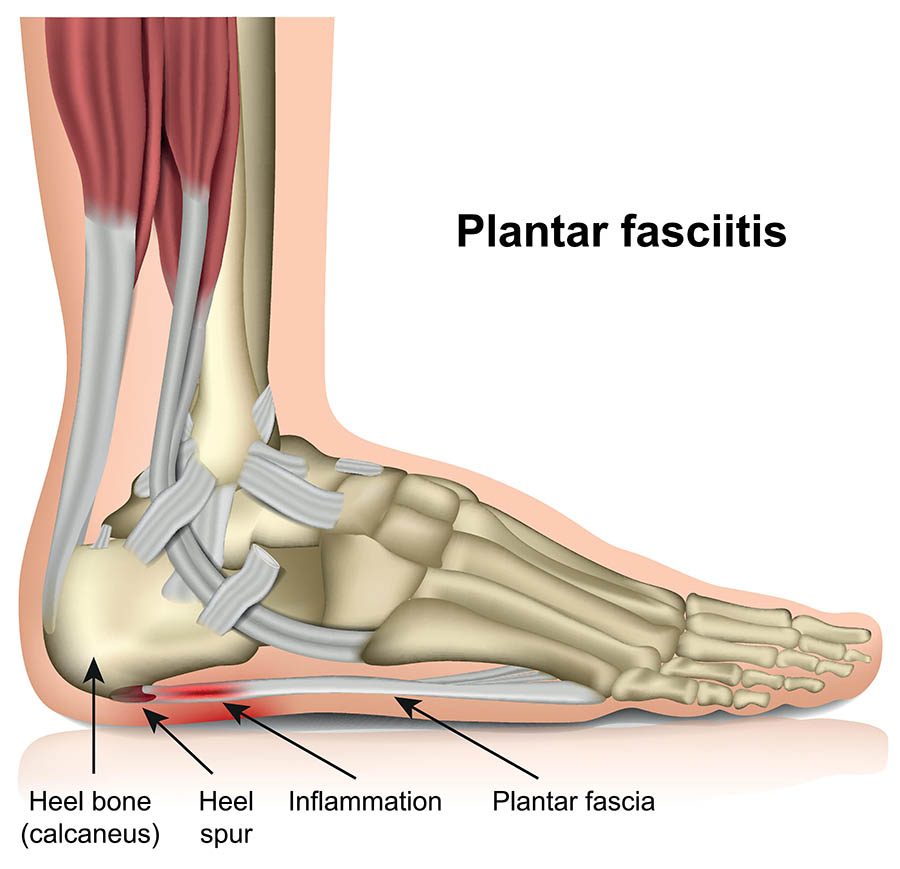

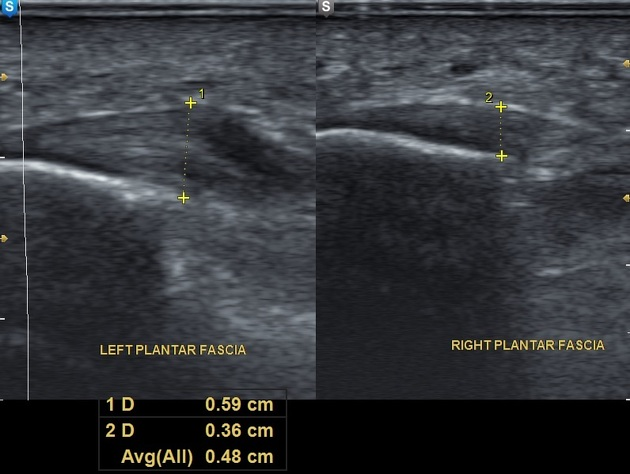

Plantar fasciitis is the inflammation and thickening of typically the insertion point at the calcaneus (heel). This can be caused by a number of factors such as heel spurs/bony spurs, changes to activity and loading over time, a recent sudden increase in activity or exercise. Diagnosis is commonly made by clinical presentation and symptoms but ultrasound may also be utilised to assess the structure and integrity of the plantar fascia – most common findings include thickening of the plantar fascia but some cases may present with a tear in the fascia.

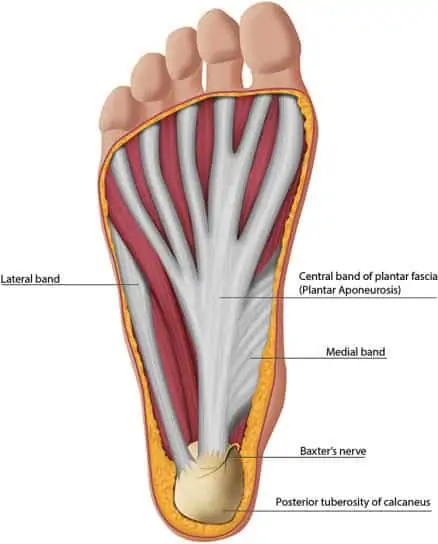

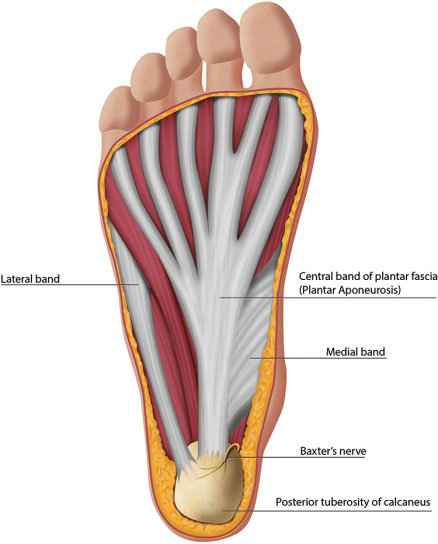

Anatomy of the plantar fascia

The plantar fascia provides a strong mechanical link from the heel (calcaneus) to the toes. It originates from the calcaneal tuberosity, the plantar fascia attaches distally, through several slips, to the plantar aspect of the forefoot. The plantar fascia can be divided into three bands: the medial, lateral, and central. While the medial and lateral bands are variable in nature, the central aponeurotic band represents the major component of the plantar fascia both structurally and functionally.

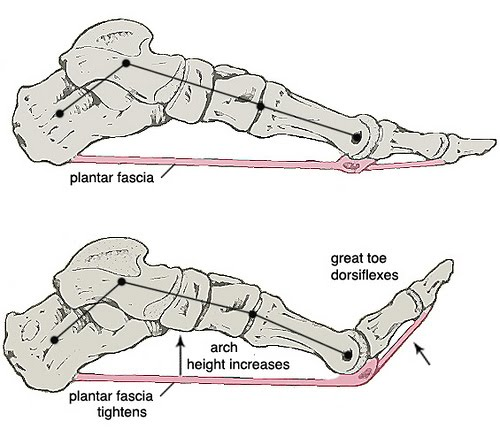

What is the role of the plantar fascia

The plantar fascia is designed to support the longitudinal arch of the foot during static stance. Because of the structure of the plantar fascia and its attachment points, when you dorsiflex your toes (pull them up from the ground) the metatarsals will plantarflex (push into the ground) which will ultimately raise the arch of the foot. This is what is known as the windlass mechanism. This occurs in non-weightbearing positions, however when you have weight on your foot the ground resists the plantarflexion force of the metatarsals, so how does elevation of the arch still occur? It occurs through a combination of supination of the foot and external rotation of the leg to maintain stability and support through the foot.

What causes plantar fasciitis?

Plantar fasciitis may be better referred to as plantar fasciopathy, as there is a lack of convincing evidence connecting symptoms with an inflammatory response. This is a process that occurs most commonly due to an overload of the plantar fascia during exercise or normal day to day life. There are a range of factors that may contribute to the onset of symptoms including BMI, footwear, anatomic features (bony spurs for example), as well as muscular factors such as calf tightness or weakness. Typically the story from clients will usually involve a sudden one off and unexpected, or sudden increase and sustained increase in exercise and activity. Some peoples definition of increase may be much lower than anothers though, for example an accountant that sits at his desk all day without an exercise routine who starts walking 5km a day could be the causative factor. But someone who walks 3km every 2nd day could likely increase to 5km a day with minimal issues. It’s important to remember that it’s all relative to the individual.

If I have flat feet, could that be causing my plantar fasciitis?

As much of a cop out of an answer as this may be, it depends. There are a lot of people out there with structurally flat feet who have never had a foot or ankle issue in their lives, and there are probably a lot of people out there with normal arch height who have a lot of issues. Unfortunately, structural arch height isn’t a great indicator of whether you will have issues. More often than not I find it depends on how the foot responds to load such as walking, jumping, hopping etc and assessing for “failures” within the system. For example someone may present with significant calf weakness that results in the foot having to take more load in compensation. Or, someone may have increased tightness in their calf resulting in increased stress placed upon the insertion point at the heel.

In my opinion, there are too many other factors at play to simply say “flat feet = plantar fasciitis”. Ultimately they may play a part and are a risk factor for the development of plantar fasciitis. If I think it may be the case I will often trial a period of time with a low dye taping technique to assess for functional and symptomatic changes. If that test is successful I am more confident that increasing structural support to the arch of the foot will result in longer term changes so it is worth investing the time and effort into potential other avenues such as orthotics (off the shelf or custom made) and a foot strengthening program.

Risk Factors for Developing Plantar Fasciitis

When assessing risk factors for conditions we will typically look for intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors. Some may be controllable and others may be outside of our control, ultimately if we take as much care of the controllable factors you will do as much as you can to reduce your risk.

Intrinsic Factors

Anatomic Factors

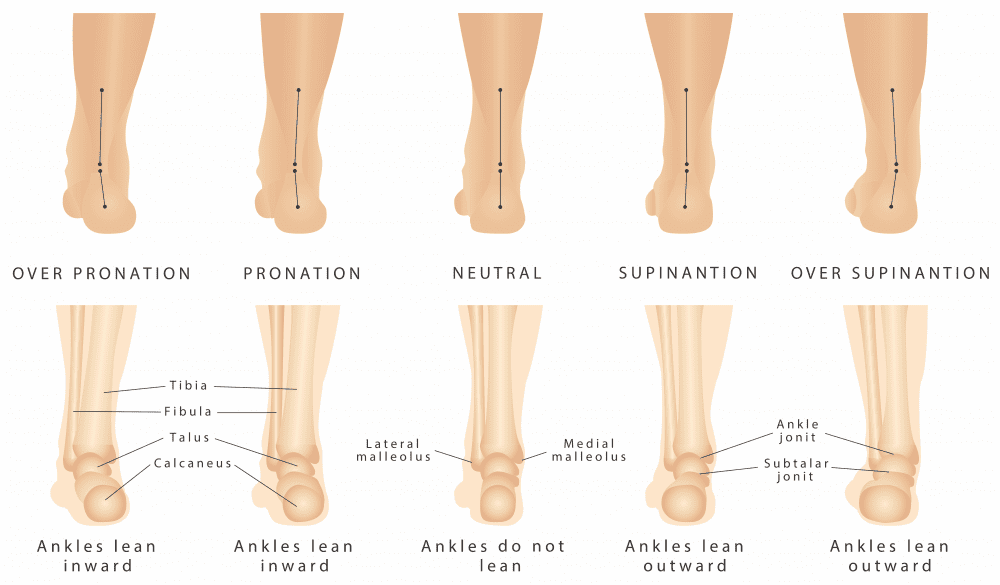

Both a structurally flatter feet and a higher arch are both risk factors for developing plantar fasciitis. The alteration in the arch results in different loading patterns through the foot when under load. The most beneficial pathway for force when walking is to land around the heel, then the foot will typically roll out ever so slightly and then roll inwards resulting in a flattening of the foot to allow you to transition towards the big toe for the last point of contact. If the arch is significantly higher or lower, changes to this pattern could occur.

Overpronation of the foot is something I often look at dynamically when assessing it as a potential cause of any concerns, but particularly when assessing a plantar fasciitis case. Pronation is a dynamic movement so it shouldn’t be only assessed in isolation, often this results in poor translation to functional activities like walking, calf raises, stairs, running etc. I will often look for two things – how much does the foot pronate, and how quickly does it happen. The speed that the foot pronates is usually the biggest tell of someone who may benefit from passive supports such as orthotics and a strengthening program.

A higher BMI is one of the most commonly cited risk factors, ultimately it means more force is translated through the plantar fascia with each step resulting in a greater cumulative force development over time potentially accelerating any degenerative factors that may be present.

A leg length discrepancy is another relatively common factor involved in these cases, a leg length discrepancy results in alterations to gait pattern, often causes changes to muscular strength and patterns between the two limbs, and ultimately increased forces through certain portions of the body. As walking is one of the most common things we do a development of increased cumulative force translated through the plantar fascia as the first point of contact for force transference, it ultimately makes sense that this is a risk factor.

Functional Factors

Calf tightness is probably the most common objective finding in plantar fasciitis cases, people report it being an issue in the mornings along with the pain. This could be a long standing issue or could be a recent development that has come on with a change in activity levels or starting a new exercise program. Increased tightness through the calf will result in a reduction in ankle dorsiflexion (the ability for your knee to go over and past your toes) and increases the tension placed upon the plantar fascia.

Calf weakness is the other key objective finding in cases of plantar fasciitis. Weakness of the calf results in less force production during walking, or higher level activities such as running, jumping, decelerating and re-accelerating that the force must be produced from somewhere else. Eccentric control (the ability for the calf to control the heel dropping towards the ground) is also a key component, if there is reduced control of this movement more force is applied to the plantar fascia over time and may ultimately result in the development of heel pain.

Degenerative Factors

Unfortunately as we get older our bodies change and adapt and not always for the better. Changes within the fat pad at the heel are one of the common risk factors seen in plantar fasciitis clients. Atrophy of this structure means there is less shock absorption provided by it which means more force is translated to the plantar fascia.

Extrinsic Factors

Training Load

Slow and steady typically wins the race, when it comes to adding in an exercise program this is almost always the case. I’ve lost count of the number of times clients have decided to start a fitness regime and gone far too hard too early and paid the price. It takes a little bit of time for our bodies to adapt and change to the extra stresses we are placing upon it, particularly structures like the plantar fascia, or the Achilles tendon. If you pay attention to your body and what it is feeling you will often be able to tell if you are pushing too hard, keep an eye out for small niggles as it’s easier to manage things early on rather than wait for it to be a debilitating issue (I’ve also made this mistake many times in past!)

It’s also important to remember that for some people suffering from plantar fasciitis may not have had a sudden increase in exercise but it may be that they were highly sedentary beforehand. In cases such as these it could be small changes that can have a significant effect. It’s important to consider everything in relation to what you have been doing. It isn’t only marathon runners that suffer from plantar fasciitis. In fact I would likely say it is more often than not the highly sedentary people with small increases who mostly present to me rather than highly active individuals who have been doing it for years.

Overuse

Whilst similar to the risk factor above this is a little bit more of a gradual onset rather than a sudden ramp up. This is typically a risk factor that causes an onset when combined with other factors such as poor footwear and weak and tight calves for example. As we use muscles and tendons it is placed under stress and causes microtears. These are beneficial as it is what results in our body getting stronger. But if I don’t let these recover and go through the process of strengthening over time this may accumulate and develop into the onset of symptoms. For some people, such as nurses for example, who are on their feet for a prolonged period of time, eliminating this factor is pretty difficult. Ultimately, in cases such as those, it is about minimising as many other risk factors as much as possible to reduce the risk of the development of plantar fasciitis.

Footwear

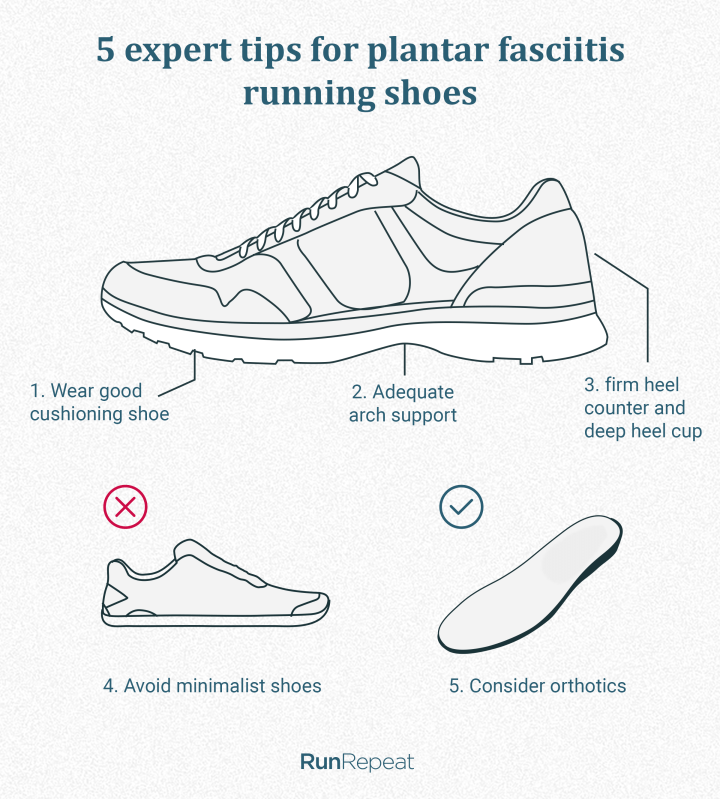

This is probably the place where people start looking first when they’ve had the onset of plantar fasciitis. A good podiatrist or physio will be able to look at your shoes and assess your gait pattern and determine whether they are the right fit for you. Looking for your wear pattern is usually the first thing I will look at when I look at a pair of shoes so I can assess for whether you have significant pronation and rolling in through the foot, or whether you can’t get across to the inside of the foot and all of your wear is on the outer edge. Neither of the two extremes is good, usually wearing through the middle of the shoe and then transitioning towards the big toe is optimal pathway to reduce your risk of preventing heel pain and reducing load on the plantar fascia.

Unfortunately making blanket recommendations for the best shoes is pretty much impossible as it really depends upon the structure of a persons foot as well as their strength, mobility, and control of pronation. Some clients may respond really well to a “motion control” shoe that has arch support, but for others that may be the complete opposite of what they need and may make the situation worse. A thorough assessment is ultimately needed to make any concrete recommendations for the best footwear for you.

How is plantar fasciitis diagnosed?

Most commonly plantar fasciitis is diagnosed via a combination of key subjective and objective testing factors. Imaging may be used in some cases of continuing plantar fasciitis that isn’t responding to typical management strategies to assess whether there may be a bone spur, a tear within the plantar fascia, or any other potential confounding factors that may not quite be getting optimal management. The most common factor in diagnosing plantar fasciitis is the distinctive heel pain first thing in the morning that clients experience. This pain can often be quite severe and often occurs on each and every step. The area of the symptoms is also quite distinctive and can be used as a differential factor between this and a few other presentations. With regards to physical testing, the Windlass Test is the most commonly used to assist in diagnosis. In a weightbearing position the physiotherapist passively extends the 1st toe and assesses for a pain response. Otherwise most of the assessment should be assessing for muscle function such as strength and flexibility, as well as assessing the functional capacity and load tolerance of the plantar fascia to assist in determining the extent to which they can perform an exercise program.

What are the symptoms of plantar fasciitis?

The most commonly reported symptom, and usually everyone’s least favourite, is the heel pain first thing in the morning, every morning. Usually this will settle within 30min to an hour but it can often make walking around in the morning quite difficult. The pain is typically located right around the heel (calcaneus) and correlates to the origin of the plantar fascia upon the heel. Clients will often report similar episodes of heel pain throughout the day if they have been sedentary for a period of time – a great example would be an office worker that sits down at their desk for a few hours and then gets up for lunch and reports similar heel pain that they felt in the morning but less intense.

Some people may report sensations of stiffness within the plantar fascia, typically I would say this symptom occurs in the earlier stages of plantar fasciitis but can also present later on in treatment when the heel pain in the mornings has reduced. The stiffness of the plantar fascia will often reduce relatively quickly (15mins or so) once you have gotten moving.

Common other symptoms may include stiffness or tightness sensations through the Achilles tendon or the calf muscles. This could often be seen as an early warning sign for the potential onset of plantar fasciitis particularly if you can correlate it with a sudden increase in exercise or general activity.

Should I get a scan for it?

Sometimes yes, sometimes no. I would say in most cases it isn’t necessary and the optimal management pathways are adequate to treat most cases of plantar fasciitis. For people who the typical treatment doesn’t work for, or for people with significant length of symptoms an ultrasound is often the first choice imaging modality. X-ray may be utilised to assess for bony spurs but this should also be picked up on an ultrasound.

Ultrasound is utilised to assess the structural integrity of the plantar fascia, for example it may find a small tear within the plantar fascia which would alter treatment strategies and can assist in explaining why it may be an unresponsive case. More often than not the main finding is thickening of the plantar fascia. This is often not a “new finding” and will often have been present for some time prior to the onset of symptoms of plantar fasciitis such as the morning pain and localised sensations. Note in the image below the thickened appearance on the left that isn’t present on the right hand side.

MRI may be used in some cases, but often isn’t required as ultrasound is typically sufficient. Given the increased cost and often waiting times for accessing an MRI compared to ultrasound typically the benefits of the MRI don’t outweigh the cost and extra time to access the information.

Why is it so damn sore in the mornings?

Plantar fasciitis is like some other conditions such as Achilles tendinopathy where it is hella sore in the mornings for about the first 30 or so minutes. It is a pretty hallmark sign of plantar fasciitis and it’s one of the most common questions we get asked as physiotherapists. Unfortunately the plantar fascia is one of those areas of the body that doesn’t respond well to long periods of sedentary activity (sitting for hours at a desk, or sleeping), these pretty much always make it worse when you first get back up. Because of the overload issue that causes the pain in the first place, these tissue changes result in a “stiffening up” of sorts of the local tissues at the site. This is part of the turnover from general day to day activity, or sporting activity. In regards to Achilles tendinopathy, there is around about a 48hr turnaround in tissue changes before it returns to it’s baseline level.

The best thing you can do to minimise your morning pain is to monitor what you do during the day and how that then correlates to symptoms the next morning. If it’s really sore and you struggle to walk, take note and take it a bit easier. Alternatively, if you wake up feeling pretty good, take that as a sign you can do a little bit more.

How is plantar fasciitis best managed?

To best appropriately manage your plantar fasciitis podiatrists and physiotherapists would be your best port of call. Podiatrists may be able to potentially craft a pair of custom made orthotics if necessary (otherwise off the shelf can be just as effective) and may also be able to assist in prescribing a home exercise program to help manage your symptoms. Physiotherapists can perform everything as above (except custom orthotics in majority of cases) but are able to also perform a wider variety of hands on techniques and may have a slightly better awareness around exercise prescription guidelines.

Ultimately optimal management combines hands on techniques to maximise calf, foot, and ankle mobility, a comprehensive and individualised exercise program to improve tissue load tolerance. Adjuncts such as taping, dry needling, and other such techniques can be utilised if needed but the core of your treatment should be an exercise program.

At home pain relief options

If I had a dollar for every time people tell me they don’t like using pain relief so they just tough it out I don’t think I’d need to be a physio anymore. Using pain relief is in my opinion one of the best strategies to help in managing plantar fasciitis. It can assist in helping you mobilise normally, can reduce flareups in both intensity and frequency. Your GP and local pharmacist are your best options to discuss the best pain relief options with as it can often depend upon a lot of different factors such as what medications you are currently taking, how severe flare up symptoms are, as well as the general pain levels throughout the day.

At home management techniques

Rolling with an ice water bottle would have to be one of the most common at home techniques for managing the pain and stiffness associated with plantar fasciitis. To do it, simply freeze a plastic water bottle overnight – a thin walled bottle would be the best option as it allows for a greater transference of the cold to the foot, then simply sit down and place the water bottle under your foot and roll the bottle back and forth. Most benefit is typically gleaned from rolling near the plantar fascia insertion near the heel as well as through the middle of fascial band through the middle of the foot.

Stretches, as I will detail below, are probably your second best choice for at home management techniques, the most common area needing stretching is the calf, and then secondly would be the foot. Some people may benefit greatly from rolling through the foot with their ice water bottle and then doing their stretches afterwards.

Foam rolling through your posterior chain (calves and hamstrings) is probably option number three. This is a great way to reduce muscle tone through areas that may be restricted. To get the best bang for your buck – couple your foam rolling with stretches, do your foam rolling beforehand, and then your stretches after.

Strengthening and Stretching

These are ultimately the key to beating plantar fasciitis, any good physio worth their weight will tell you so. A targeted program is needed, and needs to be prescribed at the right amount of intensity and workload to have maximal effect, without creating a significant increase in symptoms.

Strengthening

The aim of strengthening programs is to improve the load tolerance and output of tissues – whether that be tendon or muscle. Some cases of plantar fasciitis may be incredibly irritable, so starting with a heavy gym program probably isn’t going to be the best option out there. There are three stages of progression types for muscles – isometric contractions, concentric/eccentric, and plyometric work. When adding in exercises or developing an exercise program for plantar fasciitis cases it’s important to monitor the 24hr pattern of symptoms to ensure there isn’t a significant increase in morning pain.

Isometrics

An isometric contraction is simply a contraction of the muscle where there is no movement. The best choice for this is to stand on the edge of a step or on a ledge and have the base of your toes on the edge and work on building the time of the hold to 4×30-45sec per repetition. These are usually best performed after warming up in the morning, lunch time, and then a night time just before you are about to go to bed. If you don’t have access to that you could simply perform double or single leg calf raise holds building to the same time and length holds. A simple progression on from this is to add a rolled up towel underneath your toes. This simply increases the tension placed upon the plantar fascia and requires it to tolerate more load.

Concentric/Eccentric

This forms the basis of pretty much any strengthening program you will ever receive, whether it be from a personal trainer, exercise physiologist, or physiotherapist. Concentric and eccentric muscle contractions require the shortening and lengthening of the muscle under load. You can bias one contraction style over another completely dependant upon your goals for the exercise.

The best progression on from the isometric calf raise is to start with double leg calf raises and progress your way to being able to perform them single leg. Typically I like clients to be able to develop endurance and strength in their calves so will vary repetitions and potentially add weight if needed.

The next progression on would be to do exactly as we did with the isometric calf raise and add something underneath the toes to place them in an extended position. For clients wanting to perform higher level activities such as running, team or individual sports, sports involving jumping, I would highly recommend you work on a pathway involving weighted calf raises in both a seated and standing position to target both the gastrocnemius and soleus.

Plyometrics

Last but not least is plyometrics, probably the most forgotten but potentially the most important for athletes. Plyometrics are about explosive, bouncy movements. Think hopping or jumping on the spot. We want to develop efficient tendons and muscles to be able to perform these movements quickly. A great first intro is walking either on the ground or up and down stairs on your toes and not letting your heels drop when you put weight onto your foot. Simple progressions could include skipping, jumping and hopping on the spot and then progressing to jumping forwards, then to forwards and backwards, as well as to both sides. With plyometrics the biggest progression is in the speed and velocity of the movement, you don’t necessarily have to look to add weight just look to make the movement faster, add a direction to it, or increase the range of the movement (e.g. drop jumps).

Stretching

Everyone loves stretching right? Every client that I give stretches always does them perfectly, the right amount of time, the right position etc, or maybe that’s just what my lecturers told me would happen at uni? Unfortunately people don’t love stretching, it takes time, it takes commitment, and it takes diligence, you don’t get fast results. But, stretching is probably one of the best things you can do to assist in managing plantar fasciitis. Maintaining mobility through the calf is essential as well as maintaining soft tissue length through the foot. Starting with individual stretches for the calf and the foot and then working your way to combined stretches using a stretch band or even a strong resistance band can be the best way to go. For a combined stretch, place the band over your toes and hold onto either end of it, pull the band up so that you stretch the calf as well as getting extension of the toes at the same time.

Taping

Regarding immediate pain management strategies and ways to improve your function, not too many things top taping techniques for plantar fasciitis. My most common strapping that I do for these clients is called a low dye taping. It’s a pretty commonly utilised technique around the physio world to assist in supporting the medial arch of the foot. The taping technique is relatively simple to perform and is basically just 3 pieces of taping applied repeatedly so it does use a little bit of tape, but physios love tape right?

Orthotics

If a low dye taping works well for you, exploring the avenue of orthotics and shoes/thongs (such as Archies – a picture of them is below) is probably a very good idea. Archies are an Australian brand of shoes that I have heard great reviews about from both a comfort perspective as well as pain relief throughout the day for a pair of casual shoes that you can wear just about anywhere. With regards to orthotics, hopefully I don’t get in too much trouble from podiatrists here, but I think a good quality pair of off the shelf orthotics can provide a significant portion of the effect that custom made orthotics can give at about 10% of the price. Unless you have some significant movement changes, or significant structural changes in your foot, that would maybe be a case where I would opt for a custom pair, otherwise I would generally recommend off the shelf in most cases.

Can you prevent plantar fasciitis?

I don’t know whether you can truly “prevent” plantar fasciitis, I think there are a lot of factors at play that could truly make me say it’s a preventable condition. What I would best recommend is that if you are kickstarting a new exercise routine, slowly work your way in. Particularly if we are talking about an exercise routine that involves a lot of running or jumping. Secondly, live a healthy lifestyle regarding your diet, hydration, and good sleep, while these won’t magically make you stronger, improving your recovery if you are exercising is the key to maximising your performance.

If you are getting into running make sure you pick up a good piece of footwear, it doesn’t need to be the new $350 pair of Nikes, but maybe don’t go for the $30 pair from Kmart either (they have some great deals but I don’t know whether shoes are their forte). In my personal experience the Nike Pegasus is a solid range of shoes for a neutral pair, while the Brooks Glycerin GTS is a good shoe for a little bit of arch support that isn’t too bulky. Look for a shoe with good cushioning as this can help take some load away from the body if you are just starting out.

How long does recovery usually take?

Longer term symptoms can take months to settle, in these cases it is all about developing the load tolerance, and unfortunately usually we have to start from quite a low level of loading and work our way up. This process takes time and dedication from both myself and my client.

Shorter term symptoms as much as a few weeks can be much easier and quicker to manage. Firstly we have to settle the symptoms with deloading the area and utilising hands on techniques. Our exercise program will usually be a little bit more comprehensive, whereas in longer term clients it may start smaller and build up.

Recovery can often take anywhere from 1 week to months dependant upon a lot of factors, but often I find the most common factor changing the timeline is how long symptoms have been present for. So if you get symptoms, it’s best to get it seen to earlier rather than later!

Latest Blogs

- Lifting Technique “Never Lift with a Bent Back” – Why Those Words Make me Shudder

- When should I see a Physio?

- Adductor Strains – A Footballers Worst Nightmare

- Hamstring Strains – Frustrating, Recurrent, Our process for how we can help you

- Gluteal Tendinopathy – It’s a Real Pain in the Ass

How can we help?