29 Aug Patellofemoral Pain – isn’t that just knee pain?

Patellofemoral pain is one of the most common presentations of knee pain we see as physiotherapists. But what is it? Is it just a fancy name for knee pain (I feel like it kind of is sometimes)? What tissues are actually injured? What causes it? Can I prevent it? Why does it seem so common in teenagers?

What does the knee joint look like?

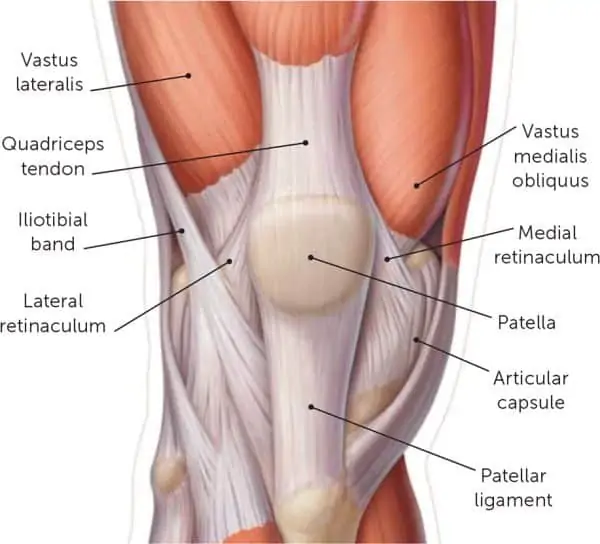

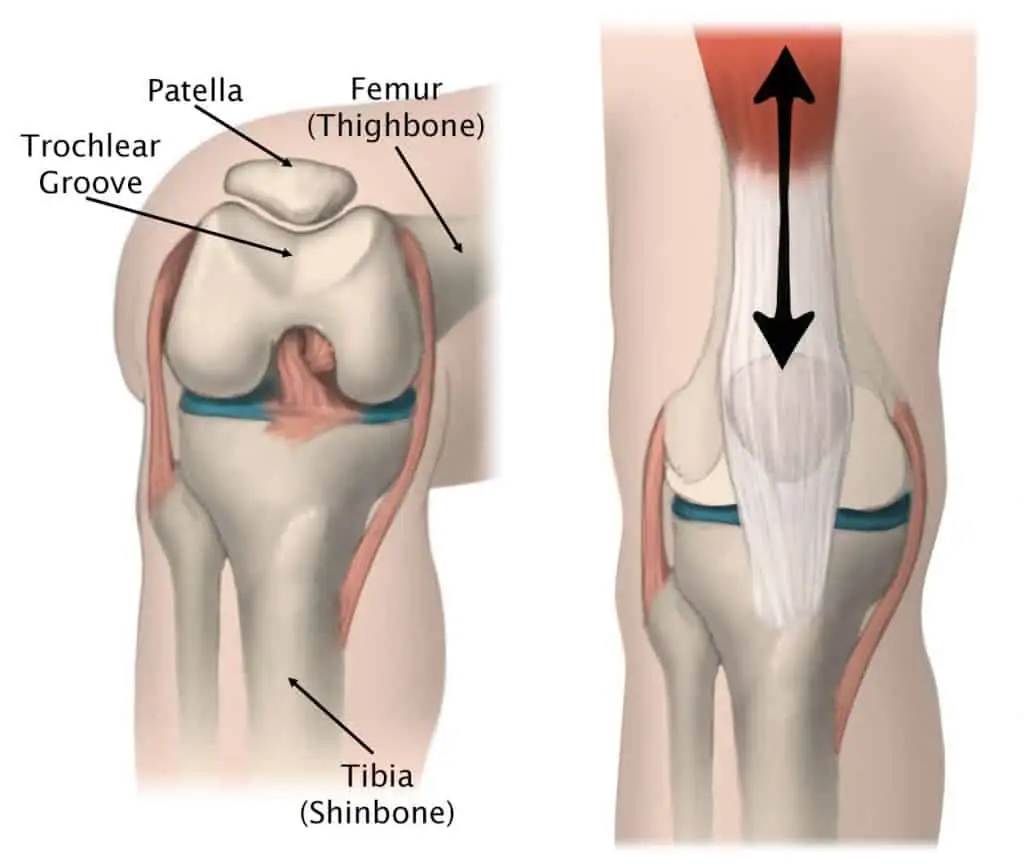

The knee joint, more technically known as the tibiofemoral joint is where the tibia and the femur meet. The fibula, the outer bone running alongside the shin does not articulate with the knee joint. It serves as an anchor point for ligamentous and tendinous structures instead. The tibiofemoral joint is a hinged joint, and allows for flexion, extension, and internal and external rotation.

The patellofemoral joint is the kneecap, it sits within the trochlear groove, allowing for freedom of movement as the knee bends and extends. The kneecap has attachments to the patella tendon (below the kneecap) and the quadriceps tendon (above the kneecap), because of this, the kneecap can be moved medially and laterally by your hands. This freedom of movement does mean the kneecap is predisposed to lateral dislocations, but is supported by a range of structures medially, namely the medial patellofemoral ligament which prevents lateral displacement of the kneecap.

What causes the pain in patellofemoral pain?

Knee pain can have many causes, with potential diagnoses such as patella tendinopathy, ITB syndrome, meniscus tears, ACL injuries or other ligament tears, or simply degenerative changes such as osteoarthritis. Fortunately, in most cases of patellofemoral pain there is no structural injury. The cause of symptoms is an increase in load at the patellofemoral joint which will eventually reach a threshold where the body will produce a pain response. In some cases there may be some degenerative changes to the surface on the back of the kneecap which may contribute to symptoms but this is typically in middle to older aged adults. Biomechanical changes to the way you move are often reason for an increase in symptoms. Commonly, the cause will be occurring above or below the knee, at the hip or foot respectively. In most cases, just treating the knee itself, will not fully resolve symptoms.

What are the contributing factors?

Common contributing factors to the development of patellofemoral pain include:

Reduced hip strength

Hip strength is an important component in controlling femoral rotation. The gluteals and deep hip rotators assist in reducing excessive adduction and internal rotation forces at the knee joint. When these two forces combine, it will reduce the area in which the patellofemoral joint is able to distribute the force. Ultimately, one occurrence won’t result in symptom development, but over time with increased pressure build up symptoms will begin to appear. This assists in explaining why clients are often unable to describe a mechanism of injury or a moment in time that their symptoms started.

Increased stiffness to the front of the ankle or calf tightness

Reduced ankle dorsiflexion is a common restriction in knee pain clients, and can often occur after surgeries such as ACL reconstructions due to the potential for reduced mobility and subsequent increase in joint stiffness or muscle tightness. Reducing ankle range of motion will result in an increase in total joint forces occurring at the knee when under load. In situations where this is the main driver of symptoms, simply treating the knee will provide inadequate relief, as this won’t affect the reduction in ankle range of motion.

Increased foot pronation

Foot pronation is often demonised quite unfairly, too often I hear of people diagnosed with “excessive pronation” or “flat feet” where this may not necessarily be the case. These clients are often blindly prescribed orthotics and never seen again. Foot pronation is a necessary part of running and is a force absorption strategy and allows the foot to transition to the 1st metatarsal (big toe) to produce power on push off. Without this pronation, we can only push off from the midfoot, or even worse, the outside of the foot. In some cases, excessive pronation can occur, simple tests such as low dye taping and then re-testing functional movements can assist in determining who is likely to benefit from orthotics. Increased foot pronation changes to trochlear groove position, much in the same way that it does with increased femoral adduction and internal rotation. Improving foot strength, endurance, and mobility is often the key, along with the potential need for orthotics if structural support is required to assist in reducing symptoms.

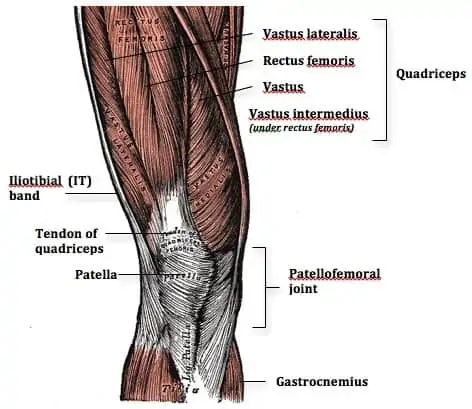

Reduced quadriceps strength

The quadriceps are vital muscles in managing patellofemoral pain, we just have to remember it’s not all about the quads. The quadriceps are integral in absorbing load during activities such as decelerating, landing from a jump, or changing direction. If the quadriceps aren’t strong enough they are unable to absorb as much force as may be needed, as such this results in an increase in the total joint force occurring at the patellofemoral joint.

Ultimately, these are just a few of the potential avenues that patellofemoral pain may occur and is not meant to be an exhaustive list, a thorough hands on and functional assessment is needed to assist in determining where your deficits are and how to best treat the area of concern.

Does it mean I have to stop playing sport?

Maybe, maybe not. It’s the physios favourite answer! Ultimately, the answer often comes down to symptom irritability, how long it takes your symptoms to settle and the functional deficits you have. In most cases we will attempt to keep our athletes training or playing, with modifications to best manage symptoms. These could include:

- Reduced training time

- Reduced intensity of training

- Use of taping, bracing, or orthotics

- Avoiding certain activities at training

- Changes of position or role within the team in discussion with coaching staff

Some level of symptoms can be expected during or after playing sport, but as long as these symptoms are manageable and aren’t increasing your risk of delaying your recovery, or risking further injury, playing sport is totally fine.

What exercises are best for this type of knee pain?

A great all round core exercise. Depending on how irritable your back pain is this may potentially be a little too tough to start in the early stages but look to progress to it soon! The easiest position to start is a simple front plank on your knees to build some endurance. You can then progress to doing it on your toes. From there the world is your oyster, you can progress the front plank further by lifting limbs off the ground to increase the demand on the core, squeeze your glutes, move your elbows further in front of your body. Or you can progress to a side plank, a great exercise to increase glute strength and endurance.

Ultimately, this program needs to be an all encompassing lower body and core strengthening program with an emphasis on your particular deficits. Addressing most of the factors above will more often than not provide a favourable outcome. It’s important to remember that the program needs to provide enough stimulus to the muscles to promote a muscular adaptation (increase in strength and size), if we cannot produce this response we either need to reconsider our aims of the exercise, increase the intensity, or select an exercise which can provide better results for you.

What does treatment usually involve?

Treatment for patellofemoral pain is highly individualised to each individuals functional and clinical deficits. Often, treatment needs to revolve around the entirety of the lower limb kinetic chain rather than just the knee itself. Common pathways of management will often include:

- Mobilisation of the knee or patellofemoral joints

- Mobilisation of the ankle or foot

- Mobilisation of the hip joint

- Soft tissue release to the quadriceps, calf muscles, gluteals, hip flexors, among others

- Taping techniques to offload the patellofemoral joint either directly or indirectly

Management of patellofemoral pain will often involve multiple of these strategies, and potentially others as well. It’s vital to remember that patellofemoral pain often involves more than just the knee. Of course, as with any other musculoskeletal condition, home exercise programs, to improve strength, endurance, flexibility, power, or balance/stability should always be performed in conjunction with hands on treatment by a physio to optimise both short term and long term results.

Can I strap my knee for patellofemoral pain?

Strapping techniques can give great results for patellofemoral pain, and there are a range of options to choose from. Ranging from the classic McConnell knee taping where the tape provides a medial force to the kneecap. Or if the foot appears to be the main driver of symptoms a low dye taping can also provide significant relief from symptoms. Tibial internal or external rotation tapings can help assist with either hip driven or foot driven presentations. Ktape, Rocktape, or any other variety of flexible tape can also provide a range of avenues to provide taping techniques for this population. Ultimately, a thorough objective and functional assessment is needed to determine which avenue will provide the most relief for you.

PRP Physio Opening Hours