04 Apr Training Load is Like Riding a Rollercoaster, just not as Fun

TRAINING LOAD IS LIKE RIDING A ROLLERCOASTER, JUST NOT AS FUN

If only this rollercoaster ride was as fun as the rides at Theme Parks

We all want our athletes to be performing at their best all the time, to do that, we first need them to stay on the pitch!

The common story that is never told in so many teams that have won championships, leagues, grand finals, or world cup finals, there is almost always an element of luck and fortune. Other teams had injuries strike at the wrong time, when the pressure ramped up players bodies failed them. Is this purely bad luck? Or is there some science behind it?

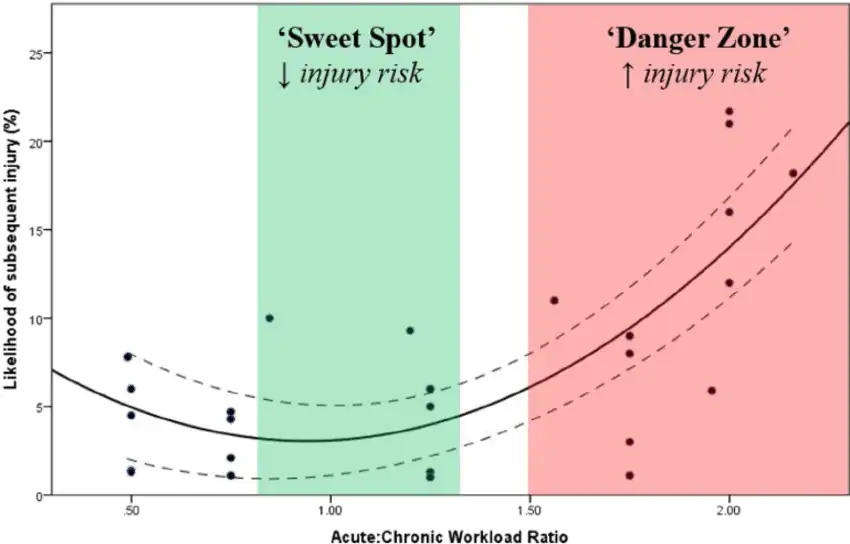

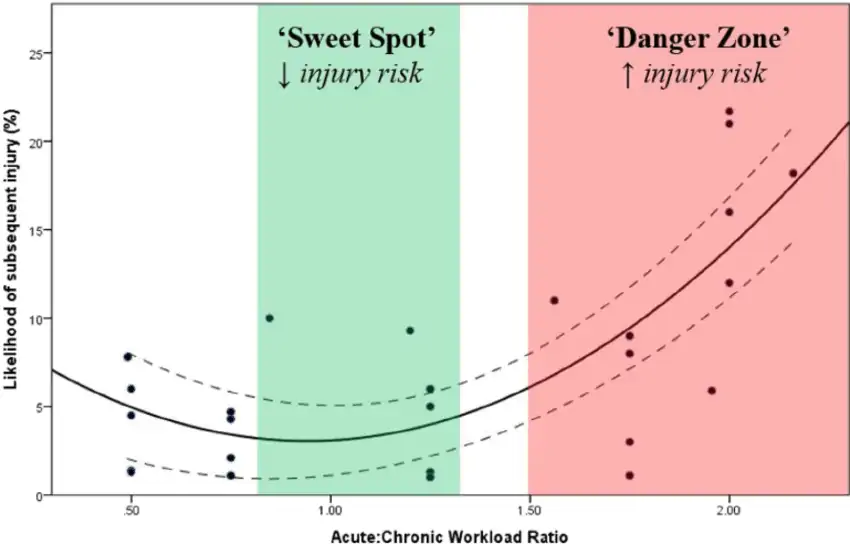

What we endeavour to teach you today, is that there is a science behind this. We cannot accurately predict when or who will get injured. But we can determine who is at more risk of injury. This can help determine how hard we can push our athletes at training and in games. We are able to ride the curve, it can be dangerous at times, and you may push the limit too far on occasion. But do it successfully and watch the rewards come flowing in.

Less Injuries = Better Performance

Better Performance = More Wins

THEREFORE

Less Injuries = More Wins

I get it, you want to play the game, or you want to train. But our job isn’t to just let you play in one game, it’s about you being on the pitch, performing at your best, without the risk of re-injury for as long as possible.

By definition, if an athlete is only capable of tolerating the average demands of a match, then they are underprepared for half of the competition they will endure. Accordingly we suggest that a key aim of preparation is to ready an athlete for any match demands within reason. Clearly these will be higher than average demands, and are typically higher than usual training loads.

– Tim Gabbett and Rod Whiteley 2017

Firstly, how do we define “load”?

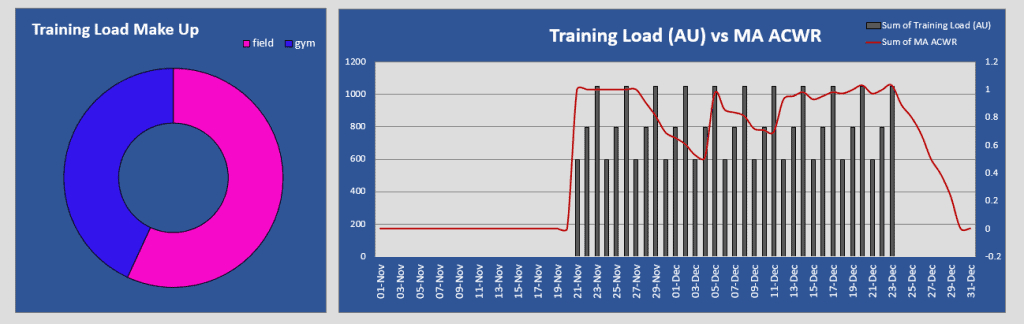

Load can be technically measured in a range of ways, it will largely depend upon what technology you have access to. Professional sporting teams will utilise GPS tracking devices to accurately quantify speed, distance, number of accelerations/decelerations, and even the number of collisions/tackles.

Every coach, athlete, or physiotherapist can determine how accurately or broadly they want to measure load.

The simplest technique utilises session intensity and session time. The calculation is: session intensity (0-10, 10 being the hardest possible) multiplied by session time in minutes. For example, a moderately tough session rated as a 7/10 that lasted for 60 minutes would have a load of 420 units.

It’s also important to note that load isn’t just external (something you do). There is internal load as well, such as:

– heart rate

– stress

– blood lactate testing and

– athlete questionnaires among others.

Research has started to indicate that there will be internal load changes BEFORE there is a noticeable change in performance of the athlete.

Is all load the same or is it specific to an activity?

This is one of the biggest problems athletes and coaches run into, they are of the belief that all load is equal. That is far from the truth! Loading is specific to each muscle, region, type of exercise, or the velocity you perform an activity at. Each parameter you change can theoretically be measured differently.

For an extreme example, consider a marathon runner and a sprinter. Both are considered athletes, both are considered fit, both perform a high workload.

BUT

If we switch their training so that the marathon runner is doing sprint training and vice versa, there will be a SIGNIFICANT risk of injury. That is because each athlete has a high workload for their specific type of training but not for the other.

What happens if I spike in my workload?

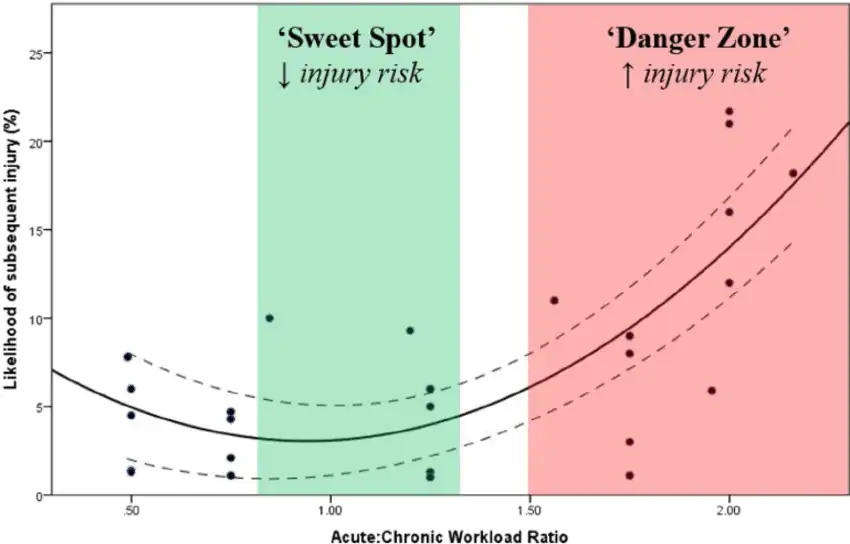

Having an increase in your workload isn’t necessarily the end of the world if you recognise it early, make proactive changes, and don’t make the same mistake again. If we remember back to the graph from the top of the page, there is a very steep slope upwards in the risk of injury. In essence, the question becomes a risk vs reward scenario. If the risk is higher, theoretically, the reward should be significantly higher also.

Consider these two scenarios, in both scenarios imagine you are coming back from a hamstring injury and you are 50/50 on it. Your physio doesn’t think you should play but the coach wants you on the pitch.

In the first scenario, it’s the 3rd game of the season, you are playing last place and it’s almost a guaranteed win.

Versus

It’s the grand final, you are the top goal scorer for the league, and you are playing against your rival team who has been in 2nd place behind your team all year.

Context plays a huge role in this situation, the risk of injury is inherently the same, but the reward is very different. Ultimately it needs to be a decision made between the athlete, coach, and physiotherapist as to whether the athlete will play or not.

If both the weight of focus of a program is primarily on injury prevention (as opposed to performance) and high loads are equated with injury, then players will constantly be managed away from their threshold.

– Tim Gabbett and Rod Whiteley 2017

My team is short on players, the coach NEEDS me to play, what happens now?

When this situation truly occurs, if a player is able to play but isn’t 100%, communication is vital.

The coach needs to be aware of the players limitations, and potential tactical and positional changes may have to be made.

The athlete needs to be aware of changes to the way they may have to play, they must be aware of the risks of playing such as re-injury, or a different injury, and they must be aware of potential warning signs of aggravation.

The physiotherapist needs to be acutely aware of the positional requirements of the athlete, and protective/preventative measures that can be put in place.

This may not seem like a lot to be aware of, but if the communication pathway falls apart, it can unravel very quickly.

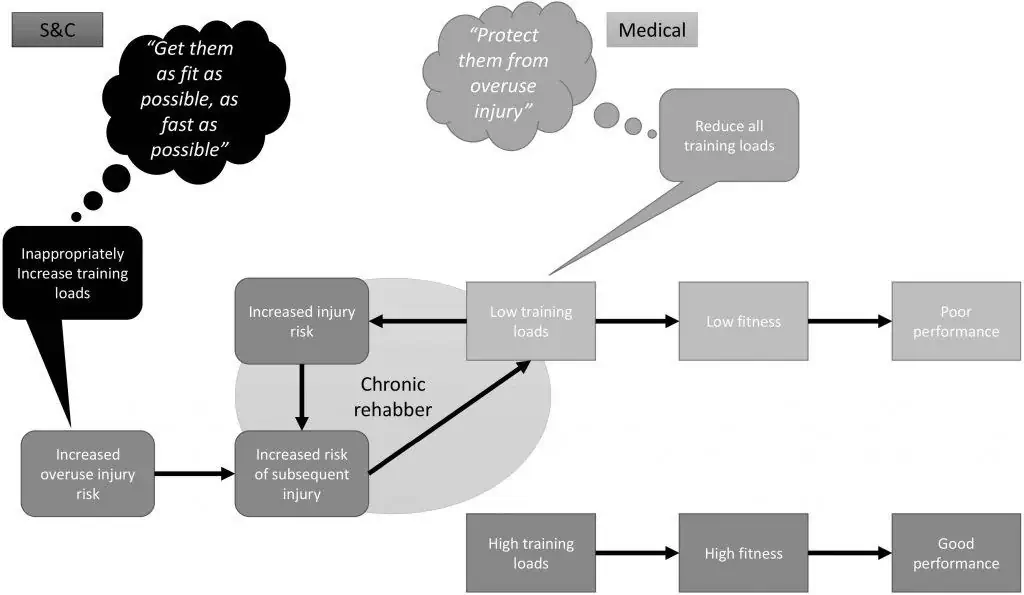

Classically in sporting teams there are three groups; the medical staff, strength and conditioning teams, and the rehabilitation group such as physios.

The medical group is told to minimise the number of injuries, inherently they decrease training loads.

The S+C group is told to maximise the teams performance, so they try to increase training loads.

The physios are trying to rehabilitate following an injury with the medical group telling them not to load too much, while at the same time S+C is telling them to load more.

This is clearly a broken system that has been described above, it is inherently impossible to minimise your injury risk to near zero, but also ask your athletes to perform at their peak each and every week.

Communication between these three groups is what is needed. At a community sport level it will often be a physiotherapist and coach performing these three roles with each one having more weighting in some than the other.

Now you are probably wanting the answer to one question by now. You are likely thinking to yourself – “Nathan, this is all fantastic information, it all makes sense. But HOW do I reduce my risk without having spikes in my workload?”

If I could create a blanket answer for everyone I wouldn’t be working as a physiotherapist anymore. Each athlete tolerates changes to load differently and needs to be progressed at their own individual rate.

What the research has shown us to date is that fitter, faster, stronger athletes are less likely to be injured. These athletes are able to maintain high training loads. Which inherently means, they can have periods of increased intensity that don’t result in significant changes in their load.